Understanding Amazon: Making the 21st-Century Gatekeeper Safe for Democracy

By Matt Stoller, Pat Garofalo, and Olivia Webb

INTRODUCTION

In 1994, Jeff Bezos left his job at the giant hedge fund D.E. Shaw, and with help from a $250,000 loan from his parents, launched a new online bookseller named Amazon. His then-boss at D.E. Shaw later explained that Bezos sought, from the very beginning, to create a monopoly. “The idea was always that someone would be allowed to make a profit as an intermediary,” he said. “The key question is: Who will get to be that middleman?” [1] Early Amazon employees confirmed this view, noting that Bezos’s “underlying goals were not to build an online bookstore or an online retailer, but rather a ‘utility’ that would become essential to commerce.”[2]

The thesis of this paper is that Jeff Bezos succeeded. His corporation is now a middleman in multiple sectors of the economy, setting the terms and conditions by which Americans conduct online commerce. The paper describes how Amazon is a commercial and political institution that has flourished within a particular regulatory model, attempts to demystify Amazon’s unfair and abusive behavior, and summarizes some of its most pernicious effects.

We also offer legislative and regulatory proposals to accomplish two complementary goals. The first is to create competition by breaking apart Amazon’s inefficient conglomerate structure into separate business lines. The second is to set clear rules for markets in which competitors operate. Such a framework is known as “regulated competition. ”[3] A regulated competition framework will eliminate the unaccountable and dangerous concentration of power lawmakers and enforcers have allowed Amazon to acquire, while retaining what consumers like about the customer experience Amazon provides. Structural separation will make Amazon’s many lines of business simpler to understand and regulate, sever conflicts of interest embedded in the hydra-like structure of the conglomerate, and help neutralize Amazon’s immense political power. Once Amazon’s lines of business are more manageable, the use of assertive antitrust, consumer protection, securities disclosure, and labor law are required to ensure a fair and level playing field for consumers, workers, and businesses.

Amazon’s power is not primarily based on providing a better set of products or services, but on exploiting gaps in antitrust, tax, privacy or other forms of law to acquire a continual set of competitive advantages. As scholar Lina Khan has written, “It is as if Bezos charted the company’s growth by first drawing a map of antitrust laws, and then devising routes to smoothly bypass them…Amazon has marched toward monopoly by singing the tune of contemporary antitrust.”[4]

Although Amazon is recognized as a powerful institution, conceptualizing Amazon as monopolistic is difficult for two reasons. First, Amazon focuses its exploitation of market power less on consumers than suppliers, who are less visible. Amazon is a gatekeeper that continually fortifies its gatekeeping capacity, placing increasingly large swaths of commercial actors into a position of dependency, and then exploiting that dependency to leverage itself into powerful positions in new markets. But consumers rarely notice, because, with some exceptions, consumer harm tends to be disguised or hard to calculate.[5] Second, Bezos uses slippery, friendly terms to describe his business, like the need to make “bold” investments for “market leadership,” sometimes using elite business school rhetoric, like claiming that he is enmeshing consumers in a “flywheel” of compelling consumer offerings.

Amazon’s market power has made Bezos the wealthiest man in the world; today, he commands a fortune of roughly $190 billion, more than the GDP of 140 countries and nearly 3 million times more than U.S. median household income. The dependency that Amazon has fostered is so extreme that it is “partnering” with governments all over the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic to police pricing gouging, showing it can alter merchant behavior far faster than government policy.

In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt argued that America was governed and “regimented” by an “informal group” that comprised the “economic government of the United States.”[6] Today, it is likely that Roosevelt would apply that characterization to Amazon, among other large corporate entities. Indeed, Harvard Law School professor Rebecca Tushnet has noted that “Amazon, with its size, now substitutes for government in a lot of what it does.”[7]

The question before us today is whether our representative government will confront Amazon’s monopoly power to protect workers, suppliers, communities, consumers, and, as Jeff Bezos’ power grows, democracy itself. Our hope is that this paper will provide important context to the growing number of policymakers and advocates who are deeply concerned about Amazon’s power over various parts of society, along with a policy framework that would effectively neutralize it.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AMAZON

Bezos started Amazon in 1994, focusing on book selling because of the unique advantages that the book market provided. Amazon soon received a significant investment from Kleiner Perkins, a prestigious venture capital firm, and adopted the unofficial internal slogan “Get Big Fast.” Bezos’s first letter to public shareholders in 1997 hinted at his strategy of taking advantage of bigness. “The stronger our market leadership, the more powerful our economic model,” he wrote. He then continued, “[w]e will make bold rather than timid investment decisions where we see a sufficient probability of gaining market leadership advantages.”[8]

Today, Amazon is the biggest book seller and book publisher in the world. “They aren’t gaming the system,” one literary agent told the Wall Street Journal in 2019. “They own the system.”[9] The day the Wall Street Journal published the story, 16 of the 20 best-selling books for romance came from Amazon’s own publishing arms. Five years earlier, in 2014, Amazon already achieved domination over the book market, selling an estimated 67 percent of eBooks, 64 percent of online sales of printed books, and 41 percent of audiobooks.[10]

Amazon acquired its power over the book market in the 1990s and 2000s by pricing its products under the cost of doing business. In 1996, the company was growing book sales rapidly, yet lost $5.8 million on sales of $15.7 million. That year, famous venture capitalist John Doerr made an investment that hit Amazon like “a dose of entrepreneurial steroids.” Bezos explained that the faster the corporation grew, the more bargaining power it would have against book distributors, so it could buy its books more cheaply. “When you are small, someone else that is bigger can always come along and take away what you have,” Bezos explained to an employee at the time.[11]

In the late 1990s, despite its losses in books, Amazon launched a toys and DVD sales division to take advantage of the increasing gatekeeping power it had over customers, who were already ordering books and thus were likely open to ordering other products, too. It spent tens of millions of dollars to be the bookstore for AOL, Yahoo, MSN, and Excite, with the goal of becoming the dominant site for books.[12] It also embarked on an acquisition strategy, acquiring Bookpages (1998), Telebuch (1998), Exchange.com (1998) PlanetAll, and AlexaInternet (1998), Junglee (1998), and invested in warehousing infrastructure, as well as a host of dot-com ventures. The only constraint was the fact that the corporation was losing enormous sums of money on its existing book business. Entering new lines of business would require an even greater capital burn.

Such a constraint, while problematic for most corporations, did not apply to Amazon for three reasons. First, Bezos had no trouble raising money on Wall Street. The corporation went public in 1997, raising $54 million in its initial public offering. From 1998 to 2002, it raised an additional $2.2 billion on bond offerings, using that money for a spree of acquisitions, among other investments. Amazon did not make sustainable profits for the first two decades of its existence; it was subsidized by its proximity to capital markets, because investors believed the corporation would eventually acquire market power to justify losses. Local stores or even large publishers weren’t just competing against Amazon, but against the mass capital of Wall Street to sustain endless losses in pursuit of monopoly power.

Second, courts and policymakers eroded legal and regulatory traditional barriers against using capital to acquire market power, which was prevented by a set of laws from the late 1800s to the 1970s. These included laws prohibiting predatory pricing or driving competitors out of the market through below-cost pricing. Other laws, like the Robinson-Patman Act, as well as laws legalizing resale price maintenance, which respectively prohibited forms of price discrimination and discounting designed to empower discounters and monopoly middlemen, were no longer being enforced, or had been repealed outright.

Third, Amazon’s money losing strategy had an embedded advantage, if it could persuade investors to sustain it. Because the corporation generally loses money according to conventional accounting principles, it avoids paying corporate income taxes. From 2008 to 2017, Walmart paid 46 times more income taxes than Amazon, despite Amazon adding hundreds of billions of dollars of market capitalization to its valuation.[13]

One way to understand Amazon’s capital burn strategy is to recognize it not as sustaining losses, as tax laws do, but as investments in monopoly power. (Indeed, even today the corporation does not break out major product lines by revenue, cost, and profit, avoiding key disclosures that might indicate the extent of cross-subsidization within the corporation.)[14] The government, through the tax code, subsidizes Amazon’s loss leading strategy.

In 1999, Amazon struck a pivotal deal with Toys “R” Us to handle the toy company’s online sales. It followed with similar deals with Borders and Circuit City, leveraging its commercial activity of selling books into becoming a platform for other businesses to reach customers.

The following year, in 2000, Amazon began letting other businesses sell on its website; up until its deal with Toys “R” Us, Amazon had been a retailer, buying wholesale from suppliers and selling to consumers, with profits derived from its margin on sales. With this shift, however, Amazon entered a fundamentally new line of business—it became a platform. As a platform, its profits derived from its ‘match-making’ role (similar to eBay) and tendering sales services, like offering fulfillment.

In this role, Amazon acquired data about other businesses through wholesaling of logistics for branded chains and its third-party merchant platform, free of restrictions on its use. That same year, Amazon began structuring its architecture to roll out what would become Amazon Web Services, its cloud computing division.[15] By this time, the corporation had adopted many of its major lines of business and strategies, and policymakers, to the extent they observed Amazon’s burgeoning growth as a policy question, largely saw the corporation’s expansion as a testament to innovation rather than monopoly power.[16]

In 2002, the corporation started to use its power against external suppliers, extracting significant concessions from the United Parcel Service, or UPS. Amazon demanded bulk discounts, and then stopped using UPS’s services when executives refused. “In twelve hours, they went from millions of pieces [from Amazon] a day to a couple a day,” said one Amazon official.[17] UPS caved. Amazon eventually set up special secretive arrangements with the U.S. Post Office, at advantageous prices through what is known as a “Negotiated Service Agreement.”[18]

Amazon also focused on ensuring its workforce had little collective power by imposing assertive tracking systems on its workers while vehemently opposing the formation of unions. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Amazon hired tens of thousands of low-wage workers in a high-turnover model.

Journalist Brad Stone noted that Amazon could be a “cruel master,” refusing to install air conditioning in Midwestern fulfillment centers. Instead, when “temperatures spiked above 100 degrees, which they often did over the summer in the Midwest, five minutes were added to morning and afternoon breaks, which were normally fifteen minutes long, and the company installed fans and handed out free Gatorade.”[19] In 2001, Amazon closed a call center which had union organizing activity, claiming that closing it was a cost-cutting measure. Union representatives mused that the real situation was Amazon’s attempt to block any unionization, and to impose a culture of retaliation. “The number one thing standing in the way of Amazon unionization is fear,” said one union official.[20] This attitude hasn’t changed; top executives were recently exposed structuring a public relations campaign against a fired employee who sought better working conditions during the pandemic.[21]

As Amazon became more powerful, it also used a variety of coercive contractual arrangements, like non-compete agreements and arbitration clauses for workers and merchants, and allegedly engaged in wage theft and misclassification of employees as independent contractors, both of which it is being sued for. The increasingly pro-concentration framework of case law enabled Amazon’s use of these contracts; arbitration clauses in particular remove the ability for stakeholders to take claims to court or band together and bring class action lawsuits, largely due to a series of cases in which the Supreme Court radically rewrote the Federal Arbitration Act to favor financial interests. Many large corporations, including Amazon, have taken advantage of this new ability to avoid being taken to court. [22]

UPS and workers were the first to taste the sting of Amazon’s aggressive bargaining. But in the mid-2000s, Amazon ratcheted up its use of bargaining power and scale in a way that induced its first political backlash in its very first line of business – books. The corporation launched what was known internally as the “Gazelle project,” a way of getting better terms from weaker publishers, which the corporation analogized as “sickly gazelles” ripe to be killed by larger predators. It soon moved to bully the entire industry.

In 2007, Amazon launched its Kindle e-book reader, pricing e-books below cost, at $9.99 for a best-seller versus the ordinary price of between $12 and $30. It also sold the Kindle reader itself below cost. Amazon announced these prices unilaterally without telling publishers. Amazon then began charging publishers five to seven percent of gross sales for “marketing development,” and denied publishers access to pre-order buttons, appearances in search results, and personalized recommendations unless they acceded to Amazon’s terms.[23] It also launched a series of publishing ventures, soon becoming a competitor to the publishers whose work it also sold. These moves were coached in rhetoric around technological progress; “Jeff once said he couldn’t imagine anything more important than reinventing the book,” said top Amazon executive Steve Kessel.[24]

Amazon continued these tactics, as illustrated by its 2014 battle with Hachette Publishers, in which Amazon delayed shipping and pre-orders for thousands of books [25] and removed pre-order buttons from many of Hachette’s soon-to-be-released publications.[26] An estimated 3,000 authors suffered a delay or loss of income before the two companies worked out new terms. Although Hachette was able to win a few concessions, as one analyst put it, “in the end this all cement[ed] Amazon’s ultimate long-term role in this business.”[27]

In the mid-2000s, as Amazon’s role as a platform between buyers and sellers grew, Bezos also began conceptualizing Amazon’s Prime membership program, which would offer consumers free shipping for an annual membership fee. Bezos told his fellow executives about his goal. “I want to draw a moat around our best customers,” he said. “I’m going to change the psychology of people not looking at the pennies differences between buying on Amazon versus buying somewhere else.”[28] The initial differentiating factor for Amazon had been price. Now it would be Prime. Students could get a free Prime membership for a year, so that, as one Amazon employee noted, they would become “addicted to Amazon.”[29] Once again, though Amazon doesn’t break out its revenues and costs, Prime was initially a money-losing venture, designed to acquire market power.

As the corporation expanded, it also used acquisitions as a mechanism to explore new markets and consolidate control. For instance, Amazon used acquisitions to expand its footprint in online retail, acquiring clothing, shoe, and household goods companies Tool Crib (1999), Back to Basics (1999), Shopbop.com (2006), East Dane (2006), Fabric.com (2008), Zappos.com (2009), Soap.com (2010), and taking over their customers and data. Sometimes the acquisitions verged on coercive; Amazon’s 2010 acquisition of Zappos and Diapers.com (Quidzi) was a war of attrition, betting Amazon’s capacity to lose money against the smaller companies’ balance sheets. Amazon won.

Amazon used the same strategy to build its dominance in fulfillment and logistics. “In 2007, we launched Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA), a new service for third-party sellers,” Bezos told shareholders. The strategy had two purposes. One, it allowed Amazon to use its leverage over sellers to gain additional inventory. “FBA items,” he wrote, “are eligible for Amazon Prime and Super Saver Shipping – just as if the items were Amazon-owned inventory.” In addition, he noted, FBA “improves the customer experience and drives seller sales.” In other words, Amazon’s fulfillment business didn’t have a competitive advantage based on quality, but on how using it gave merchants access to Prime clientele and a presumed algorithm boost.[30]

In 2012, Amazon spent $775 million to acquire Kiva Systems, a startup using robots to increase the efficiency of fulfilling packages. At the time of acquisition, Kiva was serving Office Depot, Staples, Gap, Crate & Barrel, and other prominent retailers.[31] Once acquired by Amazon, though, Kiva let its contracts with other retailers expire and was rebranded as Amazon Robotics.[32] In 2016, one industry publication lamented that Amazon’s acquisition of Kiva left a “technology gap” in the robotics fulfillment sector; Amazon got the technology, while other retailers were left with no recourse.[33]

With its 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods, Amazon began moving into grocery markets. By tying its Amazon Prime retail membership to discounts at Whole Foods, Amazon gained a window into individual customers’ purchases across a large swath of the retail economy, linking Amazon Marketplace purchases and Whole Foods choices to each identity. Amazon is now using that shopping data to build out its own convenience stores and cashier-less grocery stores.[34]

In the 2010s, Amazon also became a major government contractor, authorized in the National Defense Authorization Act of 2018 to serve as a procurement hub for the federal government and acquiring cloud computing contracts across intelligence and federal agencies.[35] It also took advantage of little-noticed changes to trade law in 2015, which allowed ecommerce companies to broadly avoid duties and tariffs for orders under $800.[36]

Today, amid the coronavirus pandemic, Amazon is consolidating its control over online retail and fulfillment, where it is using its power over now-desperate sellers to foreclose rival logistics services.[37] Amazon made $11,000 of sales per second during the government-imposed lockdowns, while Bezos added nearing $50 billion to his fortune between January and June.

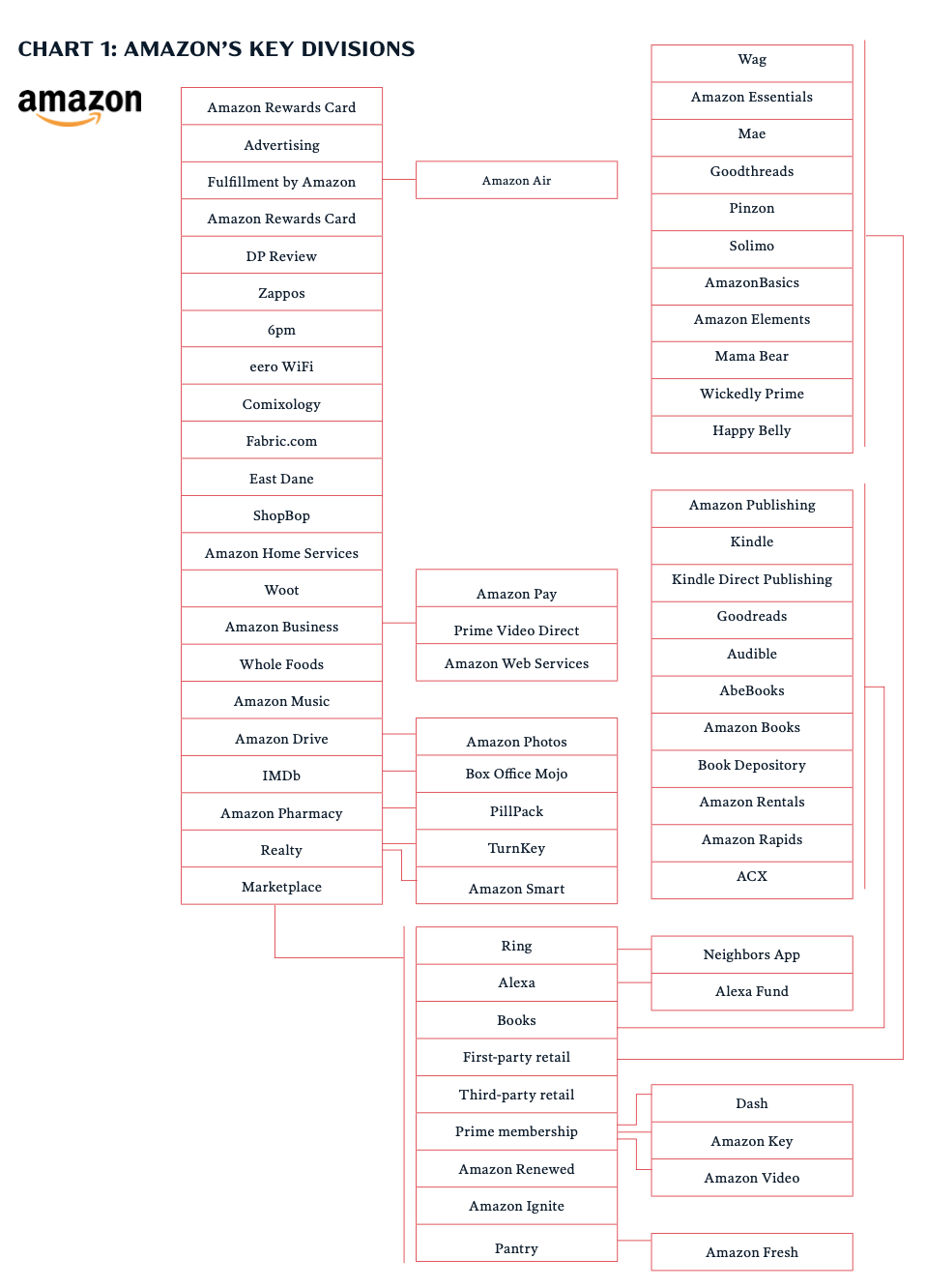

AMAZON’S KEY DIVISIONS

Amazon is far more than a retail empire and a marketplace for third party sellers. Its divisions include a movie and television studio, a cloud computing utility, an electronics maker, a supermarket chain, a fashion branch, and divisions in advertising, security, music, books, streaming games, voice assistants, fulfillment and logistics, and pharmaceuticals.

The various branches of the corporation – from Amazon Marketplace to Amazon Web Services – offer an endless stream of cash flow that enables the corporation to cross-subsidize other activities and lines of business that are not profitable. Amazon is such a significant corporate actor that the very prospect of Amazon entering a market can cause significant changes to the stock price of incumbents in that market.

Below, we describe a small selection of key lines of business to provide a sense of Amazon’s scope and illustrate how its vast reach allows it to move into new sectors of the economy.

Amazon Retail and Amazon Marketplace

Amazon is best known as an online store that sells everything from baby products to musical instruments to books to tools to software to lawn care to sporting goods products. It serves as a direct first party retailer of goods, and it also operates Amazon Marketplace, which is a platform through which third party merchants can reach online consumers, but on which Amazon also sells its own products. Though the company owns hundreds of brands, it does not release data on which ones it owns, though its most successful private label brand is Amazon Basics.[38]

In 2018, Amazon claimed it retailed $277 billions of goods, of which $117 billion were Amazon-sold products, with the remainder sold by third-party retailers.[39] No one can accurately estimate market shares for online commerce, because the Securities and Exchange Commission does not require Amazon to disclose the Gross Value of Merchandise sold on its platform.[40] But Amazon likely controls between half and three quarters of e-commerce in the U.S.,[41] including nearly 90 percent of e-books, more than 80 percent of e-readers, and more than 40 percent of print books.[42] Amazon also holds more than three fourths of all digital transactions in toys and games, household essentials, electronics, personal care, and appliances. Marketing experts note that Amazon simply is the marketplace; brands who choose not to sell on Amazon are simply “abdicating their presence” in the key online marketplace and allowing third parties to manage their branded products.[43]

Amazon Prime

Amazon Prime is often understood as a customer loyalty program for Amazon, but the point of Prime is to enhance the corporation’s gatekeeping power over online shopping. The product launched as a $79 annual fee for free two-day shipping on a host of “Prime Eligible” products. Prime Eligible products have become far more popular on the site than products that are not Prime Eligible. In pursuit of gatekeeping power over consumers, Amazon lost revenue by foregoing money customers would otherwise pay for shipping. Today, Amazon wields Prime Eligibility as a weapon against its third-party merchants; merchants who use Amazon’s warehouse and use Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) automatically get Prime Eligibility, and thus better access to customers.[44]

Amazon has added new benefits to Prime, including free video and music. Today, a basic subscription costs $119 a year and includes free grocery delivery, Prime Reading, Prime Wardrobe, Whole Foods discounts, and free Twitch content. By 2019, Prime had more than 150 million users globally. Amazon does not break out its revenue for Prime separately, so there is no way to know whether this product makes money on its own or is simply a way of tying together Amazon services for anti-competitive purposes.[45]

Fulfillment by Amazon and Amazon Logistics

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) provides storage and shipping for many of the third-party sellers who post on Marketplace. Analysts argue that Amazon effectively coerces sellers into using FBA by making use of FBA a de facto requirement to achieve the “buy box,” or the boxed location on an Amazon product page, from which 80 to 90 percent of customers make their purchases. Though Amazon denies any such tying arrangement, the corporation did acknowledge it makes FBA products more likely to become “Prime Eligible” and thus more likely to be placed in the “buy box” and purchased by Prime subscribers.[46]

Amazon Logistics is the corporation’s expanding network of third-party, contracted delivery services. This logistics network of more than 800 independent contractors provides storage, shipping, and delivery for many of their packages.[47] The network has ramped up quickly over the last few years; Amazon delivered nearly 50 percent of its own packages in 2019, approximately 4.8 million packages daily in the U.S., compared to less than 15 percent in 2017.[48]

As Amazon’s delivery network gets more powerful, it is taking market share from delivery giants like FedEx and UPS.[49] Such a delivery network adds one more potential gatekeeping chokepoint, while adding fortifications to already existing chokepoints. For instance, Amazon’s dominance as a customer of package delivery gives its delivery network an unfair advantage over rivals, since Amazon can simply preference the use of its own delivery network for its packages. Then, as its delivery network becomes dominant, it will have the ability to foreclose retail competitors from equal usage of an important logistics facility.

This network also enables the corporation to offload liability while retaining control. Amazon may choose the contracting system for delivery to distance itself from unsafe speed required to meet Amazon’s exacting standards,[50] as much as a package delivered every two minutes.[51]

Amazon Advertising

Amazon’s advertising platform is large and growing rapidly. By late 2018, the corporation was the third-largest digital ad seller in the U.S., behind Google and Facebook, and though the firm does not break out revenue, analysts estimate that it had over $10 billion in annual revenue that year alone.[52] Morgan Stanley estimated in early 2019 that Amazon’s ad platform alone was worth $125 billion, more than Nike or IBM.[53]

Amazon Advertising has gained market share quickly. By 2023, the corporation is expected to hold 14 percent of total U.S. digital ad sales, up by 10 percent since 2018.[54]

Amazon’s advertising business is propelled by three different factors unique to the corporation. First, Amazon has granular data about customers and purchases on its platform, data that not even Google and Facebook can provide. Second, Amazon Advertising has access to must-have ad space on Amazon.com, both banner ads and “sponsored products” spaces based on keyword searches, akin to slotting fees for shelf space at retail chains. Third, Amazon advertising has access to a ready base of third-party merchants dependent on access to Amazon.com and customers.

Some merchants claim that Amazon uses access to customers as leverage to force them to spend more on marketing.[55] The corporation has narrowly denied tying access to customers to advertising, but it admitted that Amazon, in negotiations with vendors, “may agree to provide certain marketing or promotional services as part of a package of terms that are acceptable to both parties.” [56]

Amazon Advertising offers a range of opportunities for Amazon to tilt the playing field in other areas. Its granular advertising data could enable the corporation to better understand what products are popular, and thus aid in the corporation’s copycat private label strategy.[57] For example, Amazon executives have discussed using its data stores, advertising business, Alexa, Amazon Music, and Audible products to enter the podcast market.[58]

Amazon Web Services

Amazon Web Services, or AWS, is likely the most profitable arm of the Amazon corporation. AWS provides cloud services for millions of customers, including the CIA, NASA, Netflix, Airbnb, Hilton, T-Mobile, and Monsanto, occupying roughly 40 percent of the cloud market in total.[59]

Risks involved in the heavy concentration of cloud computing services become clear when AWS experiences a service blackout or technical bug. In 2017, for example, a single worker inputted a typo,[60] and websites across the country went down.[61] In 2019, a server outage caused the loss of data from several customers; one commentator remarked, “Reminder: The cloud is just a computer in Reston with a bad power supply.”[62]

As of 2019, AWS comprises approximately half of Amazon’s yearly operating income,[63] providing a revenue stream – nearly $26 billion in 2018, more than McDonald’s or Qualcomm –that the parent corporation draws from as it expands into other segments of the economy.[64] While there is competition for cloud computing services, Amazon’s AWS is able to wield vendor lock-in power against existing customers, who find it costly to move to a different provider.

Similar to Amazon’s tactics on the Marketplace, the corporation’s insight into its competitors’ data allows it to view what open source software is popular on Amazon Web Services and copy that software, a practice called “strip-mining.”[65] Open source software is a concept unique to the software world; developers allow public editing or use of their code for free. Amazon disrupts this system by copying the code and putting it behind a paywall.

Deutsche Bank has picked up on comments by an Amazon retail rival who argues that AWS is subsidizing the retail side of Amazon’s business.[66]

Alexa

Alexa is the most popular voice computing platform, embedded in tens of millions of Amazon Echo and Fire devices and integrated into thousands of third party products, from Facebook Portal, Sony headphones, thermostats, lightbulbs, lamps and routers to automobiles, including GM, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Lamborghini.[67]

This technology was originally licensed from another firm and used in Amazon’s failed Fire Phone; when Bezos heard the voice-activated component, he devoted millions of dollars to developing internal voice recognition software.[68] Voice recognition technology is controversial for its invasive position; Amazon records and stores longer snippets of audio than users are led to believe, and human analysts transcribe that audio.[69]

Alexa voice recognition applications are known as skills and can be programmed to do any number of tasks, from controlling home electronics and lighting to playing Spotify to reading a bedtime story. Amazon serves as both a platform and a competitor on top of that platform, creating its own set of skills and hardware products in competition with third parties. In 2015, Amazon spent $100 million on funding start-ups building products integrated into Alexa, but some of those entrepreneurs claim that Amazon simply copied what they had created.[70]

One key problem with Alexa is the anti-competitive nature of control of such a key resource as voice computing platforms by a large conglomerate with the incentive to self-deal. A simple example is that the default music service for Alexa is Amazon Music, a service available for free to Prime members. Far from an innocuous choice, such “default bias” is a key mechanism to organize market structure in digital markets.[71]

Finally, Alexa fortifies the power of Amazon’s Marketplace by providing more customer data to the system and by giving Marketplace the ability to set only one top product for each voice command. As the New York Times reported in 2018, “consumers asking Amazon’s Alexa to “buy batteries” get only one option: AmazonBasics.[72]

Ring

Ring, formerly an independent technology start-up, was acquired by Amazon in 2018 and has become a major part of Amazon’s drive into data collection. Ring offers a subscription service doorbell with a camera that connects to an app, allowing the owner to screen visitors and observe package delivery. Ring doorbells are part of a gateway to the “smart home,” a set of digital services that include Alexa and offer more granular consumer control over the home environment, while enabling intrusive surveillance.

Amazon refuses to release exact Ring sales numbers, but the corporation has sold millions of units in just the last two years, with nearly 400,000 units sold in December 2019 alone.[73] One independent analyst found that 36 percent of American homes have installed a video door bell, with Ring as the market leader.[74]

While each Ring offers its user a camera for security purposes, when put together these cameras create a massive private surveillance network and provide data Amazon can use to improve facial recognition technology. Ring’s surveillance network has expanded as police departments request access to video footage from local residents. Amazon has also partnered with police departments, in some cases allowing them to request footage without a warrant, circumventing standard criminal justice proceedings.[75]

Amazon Studios

Amazon Studios is increasingly a significant buyer in filmmaking and distribution. In 2019, Amazon Studios spent around $6 billion purchasing content.[76] It is also in the process of aggressive hiring, ramping up its production team to 3,000 employees.[77] As with other parts of the Amazon corporation, executives are careful to leverage the huge reach of Amazon’s brand in their negotiations.

Amazon Marketplace, Amazon Music (which allows Prime members to access free music), Audible, and Twitch live-streaming services are all part of Amazon Studios’ sell to filmmakers.[78] In one example, Amazon Studios reached a deal with Rihanna to film her fashion collection’s New York Fashion Week show while simultaneously selling her lingerie on Amazon Marketplace. Amazon Studios is also a key part of the offering for Amazon Prime, fortifying the company’s control over online customers.

Amazon Retail: Whole Foods, Amazon Go Grocery, Amazon Convenience Stores, Amazon Books

Amazon operates seven different physical retail outlets, including a convenience store, two types of grocery stores, a bookstore, and an electronics store to let customers try out devices. The most important and largest is Whole Foods, a high-end grocery store chain, that was acquired by Amazon in June 2017 for $13.4 billion. Whole Foods serves as a pickup point for Amazon Prime members, is part of Amazon’s data collection network, and uses Prime as its loyalty program. The company regularly collects data on its shoppers by offering a discount for Prime members if they scan an associated barcode.

To date, Amazon’s forays into physical retail are in their experimental stage, but the corporation has created “Just Walk Out” technology as a cashier-less experience. It is attempting to sell this automated checkout service to rival retail outlets, becoming an operating system platform for physical stores. It is possible that such integration could enable Amazon to reproduce the dynamic of being both a platform and a competitor in the physical world of retail.[79] The pandemic has put these plans on hold, though the collapse of rival retailers is likely to enable Amazon to springboard into physical retail dominance.

AMAZON’S UNFAIR AND ABUSIVE PRACTICES

Amazon pursues a variety of tactics that undermine fair and open markets, harming small businesses, workers, and consumers. These include monopolization through practices such as predatory pricing, tying of products, and using third-party sellers’ data against them. Others go against guidance offered by regulators; for example, Amazon’s advertising revenue sells ad slots that seem to be in violation of the Federal Trade Commission’s 2013 guidance on deceptive search engine practices. Still others are abusive to workers, such as traditional anti-union tactics.

Below, we demystify an incomplete set of abusive behaviors and monopolistic tactics that Amazon consistently employs.

Amazon Engages in Predatory Pricing

Amazon’s anticompetitive behavior includes what appears to be predatory pricing. While laws against predatory pricing haven’t been enforced for decades, predatory pricing occurs when a company lowers prices below cost in an attempt to drive rivals from the market.[80] Predatory pricing differs from aggressive price competition because predatory pricing is not about offering a more efficient service; it is about gaining market share purely through financing losses with external capital sources or cross-subsidized through other cash-generating divisions.

The most striking example of Amazon’s predatory pricing strategy took place in the 2000s with competing retailer Quidsi, the company behind Diapers.com and Soap.com, popular sites for baby and cleaning supplies.[81] In 2009, Quidsi executives refused an acquisition offer from Amazon. In response, Amazon lowered its Marketplace prices on baby supplies, and Amazon also directly pegged its baby supplies prices to Diapers.com prices. Executives at Quidsi calculated that Amazon Marketplace lost over $100 million during three months on diapers alone. Jeff Bezos, reportedly, at one point threatened to price diapers at zero.[82] Quidsi sold to Amazon.

Regulators carefully watched corporations for predatory pricing actions throughout much of the 20th century. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, scholars began to suggest that predatory pricing was an illogical business strategy and thus did not often occur. As a result, predatory pricing case law now requires that plaintiffs prove what is called recoupment. Plaintiffs must show that the corporation in question lowered prices below cost and has plans and a plausible strategy to raise them again to recoup its lost revenue after acquiring market power. Thus, proving predatory pricing claims is virtually impossible.

Defanged predatory pricing doctrine has empowered chain stores in general, but Amazon has leveraged the decline of this legal barrier with unique capabilities. It is capable of running for decades at a loss, and it is capable of cross-subsidizing predatory pricing through its multiple business entities. Amazon Web Services, for example, can make up for lost revenue on Amazon Marketplace or Alexa. Further, shareholders are willing to give Amazon a long leash, recognizing that predatory practices may lose money upfront but will translate to long-term monopoly power and profits.

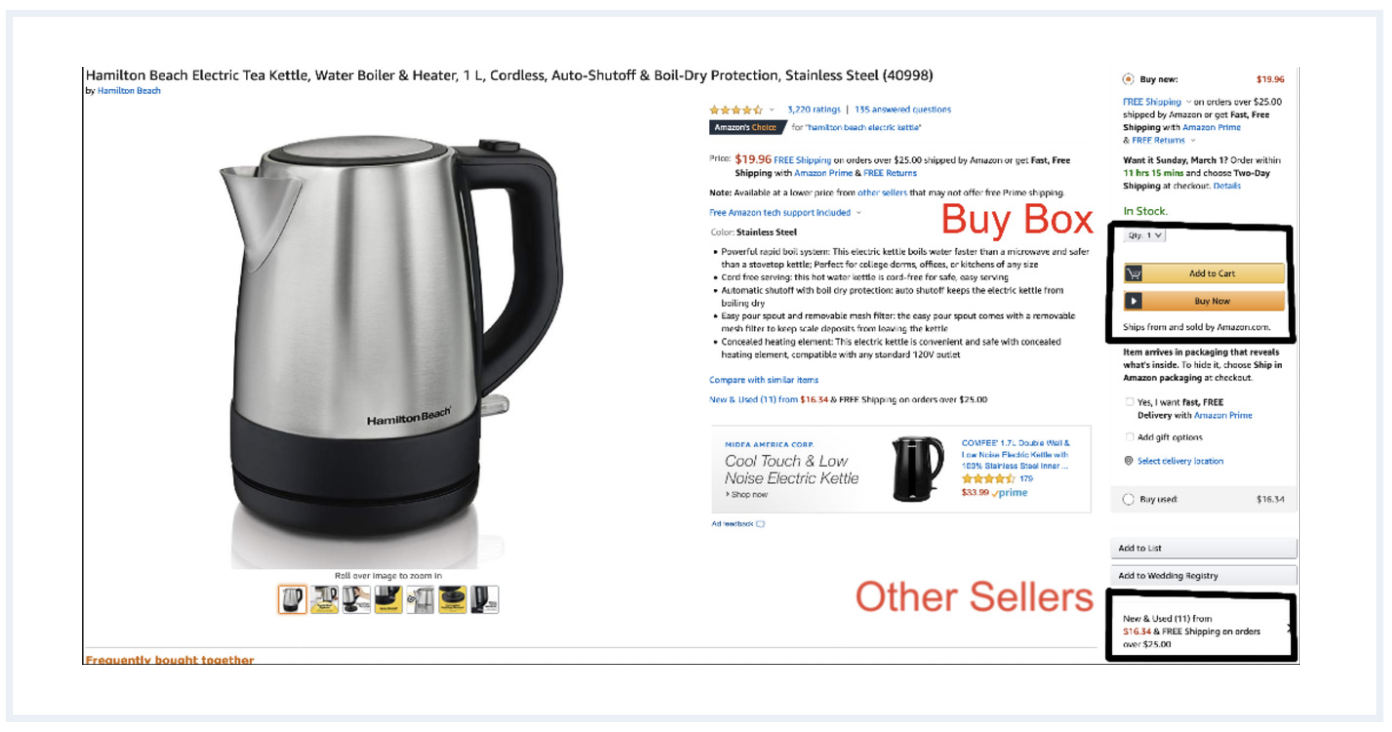

Amazon Engages in Tying and Bundling Strategies

Tying means forcing customers of one product to buy a second product in a distinct market. Third party merchants claim Amazon uses this tactic by tying its marketplace to its logistics network, Fulfillment by Amazon. The mechanism of tying is subtle, but powerful. Selling through Amazon’s marketplace means fighting over real estate with other merchants, including Amazon itself, so that your product gets placed in front of the customer when they choose to make a purchase. This important real estate on the Amazon page is called the “buy box,” which is the button on the right of the page that sets the default merchant from whom the customer will buy if the customer adds an item to his or her cart, or selects “one click shipping.” Eighty to 90 percent of customers use the merchant that wins the buy box, so winning the buy box essentially means being able to sell on Amazon.[83]

Though the algorithm for who wins the buy box is secret, independent researchers who have reverse-engineered it have determined it relies on several factors like speed, price, product ratings, whether the product is prime-eligible, and reliability of delivery. The tie to FBA happens in two ways. First, merchants who use FBA get their products to be “Prime Eligible” and thus more likely to be placed in the “buy box.”[84] Second, the fulfillment method is the single most important factor in how Amazon selects the winner of the buy box. Paying for Fulfillment by Amazon gets the merchant a perfect score on the metrics related to fulfillment. Though Amazon denies the claim of a direct tie between FBA and its marketplace services, for sellers to be able to reach the most customers, using FBA does tend to make it more likely to be placed in the “buy box.”[85]

FBA is often more expensive than alternative options, and Amazon continues to raise prices.[86] Sellers have challenged this arrangement. In November 2019, a third-party retailer wrote to Congress accusing the corporation of bundling its Marketplace and logistics services together illegally.[87] The seller noted that, by requiring sellers to use FBA, Amazon has the latitude to continue to raise prices. The seller’s internal research revealed FBA’s prices to be up to 35 percent higher than competing services.

Amazon Preferences its Own Products on Platforms it Controls

Since Amazon both runs and competes on its own platform, there are ample opportunities for it to give its own products preferential treatment over cheaper or better-reviewed products from third-party sellers. As noted earlier, it makes its own products the default on Alexa’s voice activated software, so when a customer asks for batteries, they receive Amazon’s branded batteries.

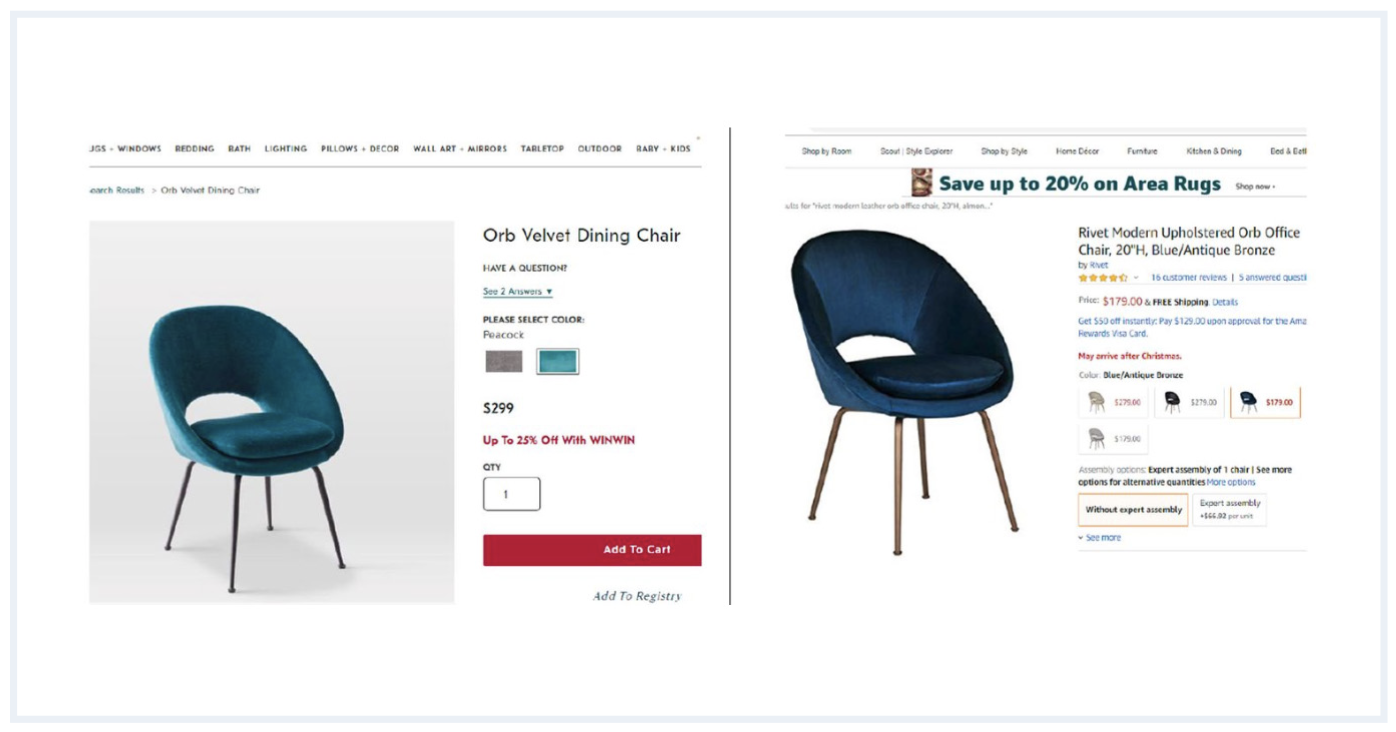

It also preferences its own products on in Marketplace, giving them the “Buy Box” positions on product pages, as shown below, even when there are other options that are cheaper or the same price. For this teakettle, Amazon has privileged its own product for the Buy Box, even though cheaper products are available from other sellers.

As one Marketplace seller put it, “If you don’t have the buy box, and you’re the same price as Amazon, you get zero sales.”[88]

On lists of search results, Amazon also places its own private-label branded products first, at the top left of the page, where buyers are most likely to click. According to ProPublica, Amazon has preferenced its own products in this way for many items, including diapers, copy paper, children’s pajamas, mattresses, trail mix, and lightbulbs.[89] Prominent positioning also allows Amazon to boost prices, since many shoppers are unlikely to scroll further for a better deal. Amazon usually charges companies to push product placement so high, but it doesn’t charge itself. In other words, it’s forgoing ad revenue to promote its own products in a bid for long-term market dominance.

Amazon Abuses Bargaining Power Against Suppliers, Platform Dependents, and Customers

Amazon uses its control of platforms on which hundreds of thousands of businesses rely in a host of anti-competitive ways. First, Amazon squeezes third party merchants on price. Amazon Marketplace is a power-buyer, meaning it exerts heavy price control over the third-party businesses that supply its platform and requiring that they adhere to its “fair pricing policy.” This policy means that the seller is always required to offer Amazon its lowest price available anywhere.

In other words, if a seller is offering a product on Amazon Marketplace and on the seller’s own website, the seller cannot offer a lower price on its website than on the Marketplace. Amazon’s fair pricing policy could also be called a most favored nation clause, or MFN. Amazon’s use of MFNs is the subject of a current lawsuit in federal court alleging Amazon is using MFN clauses despite promising the FTC it would stop.[90]

Sometimes, Amazon arbitrarily lowers prices on goods sold by third-party businesses. As the CEO of PopSockets testified at a Congressional hearing, “the Amazon Retail team frequently lowered their selling price of our product and then ‘expected’ and ‘needed’ us to help pay for the lost margin.”[91] In other words, Amazon chose to lower the price on PopSockets and then expected PopSockets to make up the difference in cost.[92]

Amazon also sets non-monetary terms in ways that privilege its gatekeeping power. For instance, Amazon closely monitors and regulates the relationship between third-party businesses who use its platforms and the customers of those businesses. Amazon packaging is standard; third-party sellers cannot use their own boxes or branding to establish independent relationships with customers, unless the business has a relatively large amount of power over a brand and can lobby Amazon to change its policy. As one seller told Digiday, “There’s probably what I would call ‘classes’ of Amazon sellers — those that are at the bottom don’t have much liberty but those that at the top do. They can command greater revenue whereas everybody else has to deal with whatever they’re given.”[93]

Amazon’s advertisements feature small business owners shipping their products with branded packaging, although Amazon rarely allows merchants to feature their own branding.[94]

Recently, Amazon has become even more assertive in using its dominance over Marketplace to take in more logistics revenue. During the 2019 holiday season, Amazon banned third-party retailers who wanted to sell through Amazon Prime from using FedEx Ground, citing slow deliveries from FedEx.[95] With little notice, Amazon upended the shipping plans of untold numbers of retailers, effectively forcing them to switch to FBA during the busiest shipping time of the year. Amazon even blocked consumers from being able to find merchants who offered faster shipping options by refusing to let sellers into its Seller Fulfilled Prime program, seemingly as a way of forcing merchants to use Fulfillment by Amazon.[96]

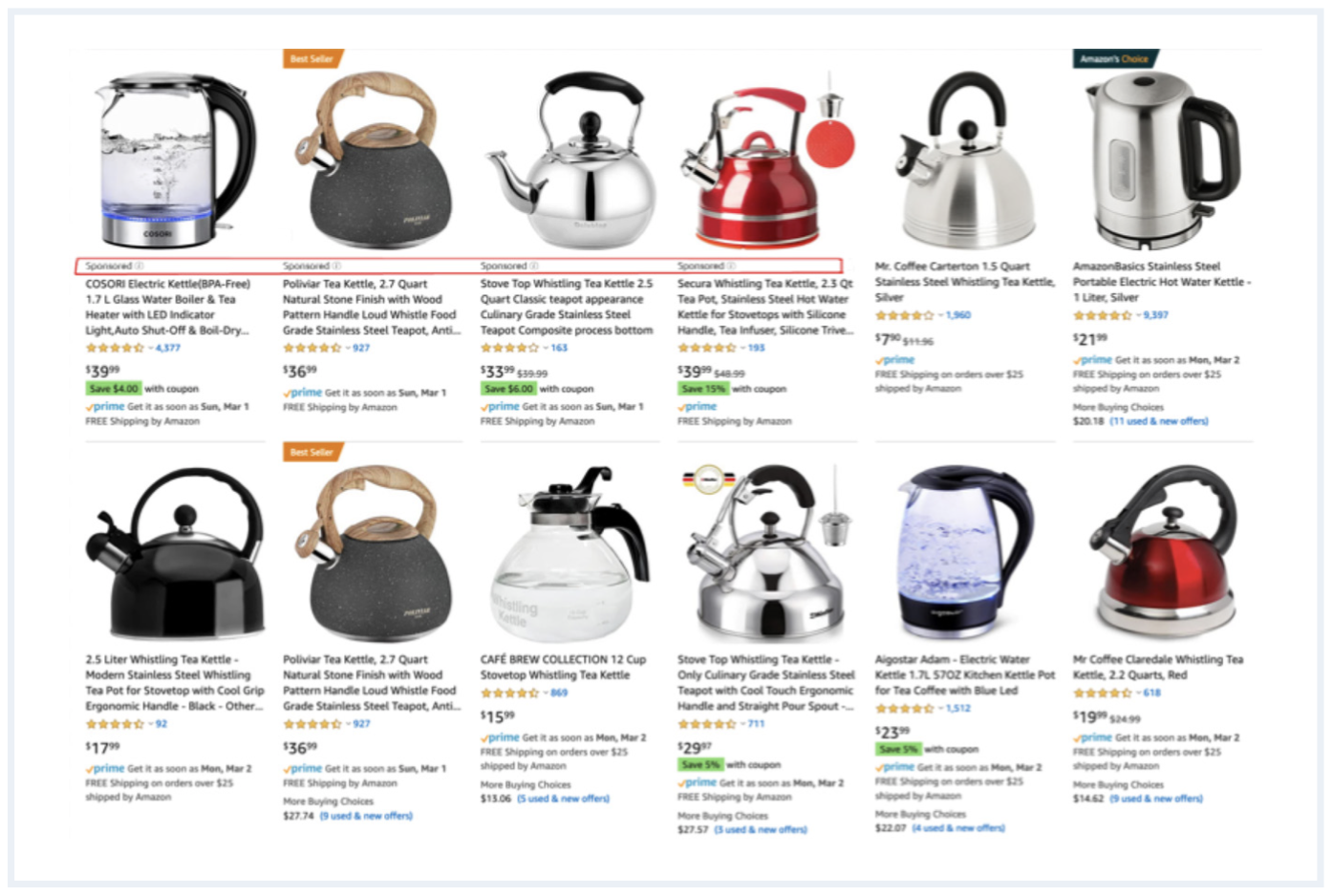

Amazon Deceptively Formats Search Results

Amazon uses its ad placement system to extract revenue and loyalty from third-party sellers, showing an average of seven to eleven sponsored listings on the first page of shopping results on desktop.[97] Third-party sellers can pay to appear higher in the list of search results for a specific keyword.[98] Then, if a customer clicks on the advertised product, the third-party seller is charged a small fee for the ad.

Amazon’s advertising seems to violate several key tenets of the FTC’s guidance on search engine advertising.[99] The FTC recommends that search engine platforms use prominent shading with a clear outline and/or a prominent border to offset sponsored results from other results. It also recommends that corporations use labels to denote advertising that are “large and visible enough for consumers to notice,” with font that is “adequately sized.”

Amazon is not compliant with these recommendations. The platform offers no shading or borders around sponsored ads, and the language is in a small, gray font.

While Amazon ads on this search page are marked “Sponsored” (surrounded by the red box, added after), the text is small and difficult to see. Otherwise, the ads are indistinguishable from the other products. But the products appearing first translates into more sales, so sellers feel compelled to pay for ads.

Amazon Surveils, Copycats, and Uses Proprietary Data Against Businesses

Amazon has data on sales numbers and revenue for each individual third-party seller, which search terms were used to access which products, how long a consumer hovered their mouse over a product link, and which products are doing particularly well. It weaponizes that data against sellers themselves.

If Amazon identifies a bestselling product, the corporation can copy it for its own sales and prioritize its version in the search results.[100] This has happened, for example, with Rain Design’s laptop stand,[101] Allbirds’s shoes,[102] and the Instant Pot,[103] along with many others. Amazon has denied such behavior, including before Congress, but an April Wall Street Journal report confirmed that it occurs.[104]

Currently, there is very little that the original seller can do to combat this legal but abusive conduct. At least two businesses, Williams Sonoma and Sonos, have publicly accused Amazon of trademark infringement and copycatting. Williams Sonoma has sued Amazon for tricking consumers into thinking Williams Sonoma-branded products are coming directly from Williams Sonoma.[105] Sonos has testified against Amazon for creating a voice-activated speaker remarkably similar to Sonos’, but the company cannot afford to sue Amazon.[106]

Amazon’s extension into home products like Alexa and Nest is the latest iteration of the corporation’s data collection practices. Amazon has deep insight into the behavior of the millions of customers using its online Marketplace, shopping at Whole Foods, using Amazon Web Services, or watching Amazon Video. Because the corporation operates all of these lines of business, it is able to use data collected from one platform (like Whole Foods) to target consumers on another platform (like Marketplace). The corporation can also use its surveillance power to copy bestselling products on the Marketplace or popular software on Amazon Web Services.

The paranoia caused by Amazon’s power over third-party retailers has also created business opportunities for the corporation. A report from the Wall Street Journal found that Amazon selectively offered special retail support to some businesses in return for an agreement allowing Amazon to acquire the retailer at any time for the fixed price of $10,000.[107]

Amazon engages in these same tactics in its AWS subsidiary. One notable example is that of Elastic, a start-up that offered free software used for data analysis, layered on top of cloud services.[108] Amazon copied the software, called it Elasticsearch, and began selling it. In an attempt to fight back, Elastic added premium features – but Amazon copied those too. An executive of another open source software copied by Amazon, MariaDB, estimated that Amazon made five times more revenue from copying and selling a MariaDB lookalike than its original company made from any of its businesses.[109]

Amazon Weaponizes Counterfeit Products

Amazon’s market position gives it leverage against all companies, not just small retailers. For large, legacy brands, Amazon has strategically permitted counterfeit products to flood its Marketplace to pressure third-party sellers. PopSockets CEO David Barnett alleged Amazon effectively forced his corporation to pay $2 million in unwanted marketing fees so that the Brand Registry team would impose measures to stop sales of counterfeits.[110] Amazon’s practice of commingling goods to ensure swift Fulfillment by Amazon has also appeared to encourage counterfeiting and fraud of third-party merchants’ goods.”[111] Low quality counterfeits eventually force large companies to either exit the Marketplace or come to the negotiating table.

For example, Birkenstock, a manufacturer of leather sandals, has repeatedly asked Amazon to police the large number of counterfeit and gray-market sandals on the Marketplace.[112] Many of the counterfeits are listed for $20 less than on the Birkenstock website, and consumers have no indication that the shoes are counterfeit or gray market. Amazon refused to take action on counterfeits unless Birkenstock allowed its entire catalog of sandals to be sold on Amazon. Finally, Birkenstock responded by pulling its official sandals from the website, although Amazon has continued to allow third-party sellers to offer counterfeit sandals on the Marketplace. As the CEO of Birkenstock said, “Amazon is the Wild West. There’s hardly any rules, except everyone has to pay Amazon a percentage, and you have to swallow what they give you and you can’t complain.”[113]

The proliferation of counterfeits not only harms other businesses by undercutting their products with cheaper knockoffs, but can directly sicken or even kill consumers. Counterfeit pharmaceuticals and supplements, for instance, have been sold on the site, as have toys and other children’s products that have been deemed unsafe.[114] One family alleges it bought a counterfeit hoverboard on Amazon that subsequently caught fire and burned their house down.[115]

In a 2019 investigation, the Wall Street Journal “found 4,152 items for sale on Amazon.com that have been declared unsafe by federal agencies, are deceptively labeled, or are banned by federal regulators.” Nearly half of those were labeled as shipping from Amazon’s own warehouses, contradicting the company’s assertion that only third-party sellers are engaged in selling counterfeit or dangerous goods.[116]

Under current law, courts have ruled that platforms like Amazon do not have liability for counterfeit products sold by third-party sellers. Currently, the California state legislature is advancing a bill that would create such liability for platforms.[117]

Amazon Requires Third-Party Businesses to Sign Coercive Contracts

Amazon requires its third-party sellers, approximately 2.5 million businesses, to sign coercive contracts that include arbitration clauses that eliminate their freedom to engage in class action suits to resolve disputes, instead appearing before arbiters who consistently side with corporate interests since they are beholden to those corporations for jobs and payment.[118] One attorney told the American Prospect that he considers the system to be “on par with North Korea in terms of fairness and transparency.”[119] Since 2014, just 24 customers, 16 vendors, 33 contractors, and 163 sellers have initiated arbitration claims against Amazon, suggesting a suppressive effect of these clauses.[120]

Amazon Uses Mergers and Acquisitions to Stifle Competition

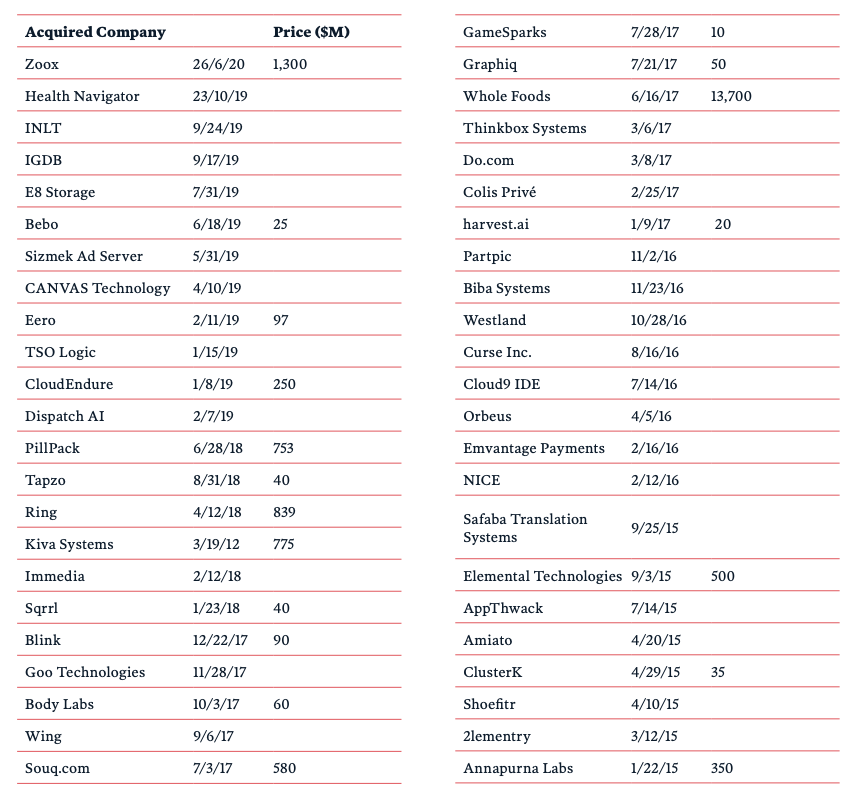

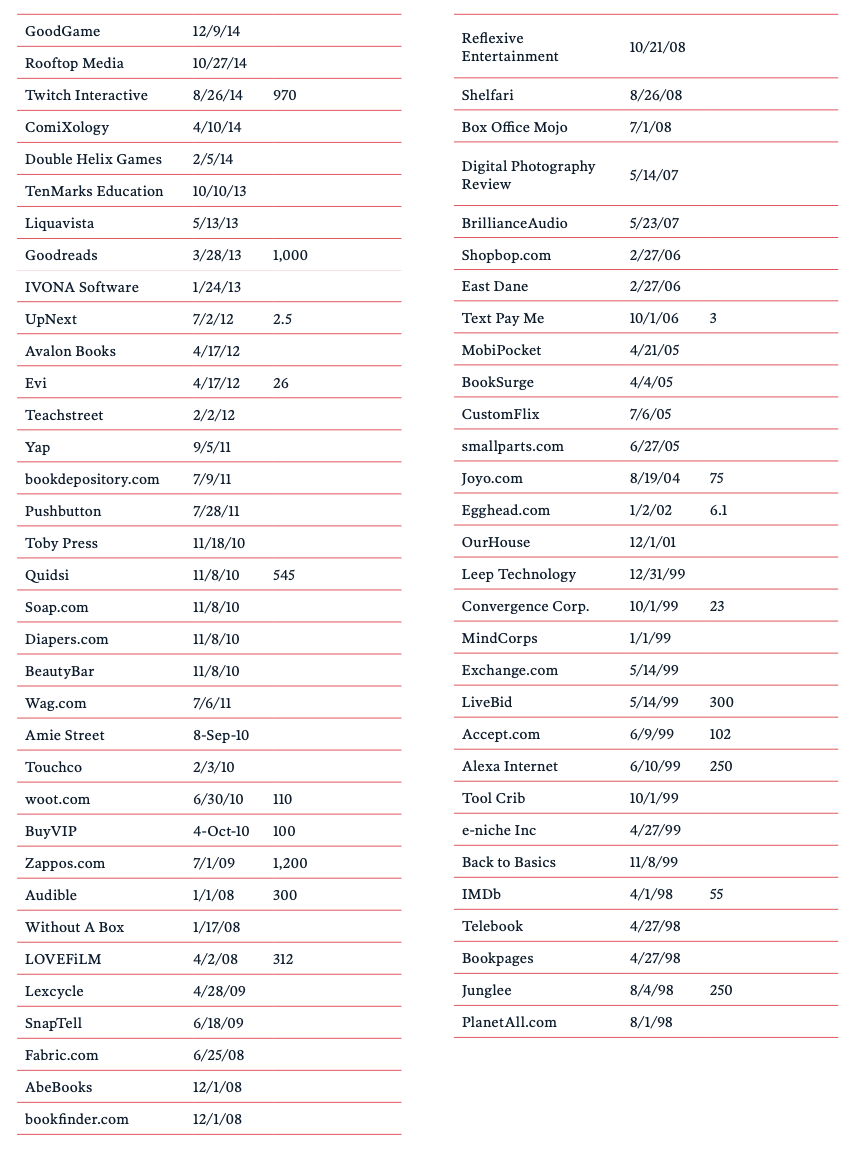

Amazon’s market power allows it to use mergers and acquisitions to move into new markets and snuff out any threats from would-be competitors. Before a merger, Amazon executives decide the market they want to take over, sometimes using data gathered using their existing infrastructure. Next, they strategically acquire competitors or businesses in that market that can provide Amazon with deeper data on the industry. Eventually, they introduce their own competing products. Through 2017, Amazon invested in or acquired at least 128 companies, though it doesn’t disclose complete data on investments and acquisitions.[121]

As detailed earlier, Amazon made many acquisitions in the retail sector in the 1990s and 2000s to prevent competitors from emerging and to gain a foothold in key sectors such as shoes and diapers. (See Appendix for a full list of known acquisitions.) In 2012, Amazon’s acquisition of Kiva Systems cut other large retailers off from a robotics system used in warehouses. Its acquisition of Whole Foods allowed it to collect reams of data on consumer preferences in the grocery space, a sector into which it is rapidly expanding. Because modern antitrust law is not equipped to handle a company like Amazon, each of these acquisitions was blessed by regulators, despite clear anti-competitive concerns.

Amazon Abuses its Workers

Amazon employs approximately 500,000 people in the U.S., many of whom are blue-collar workers filling Marketplace orders in warehouses across the country.[122] Due to aggressive tactics by the company, Amazon warehouse workers are not part of labor unions.[123] One result is that they likely suffer not only from lower pay, but from lower safety standards than the industry average. Amazon warehouse logs, where available, show an injury rate nearly double the warehouse industry average,[124] and three times the average for private companies in general.[125]

The speeds Amazon demands are punishing; one former warehouse worker told The New Yorker that “[t]here’s a constant pressure to hit your numbers…I’ve seen people who aren’t even thirty years old get injuries they’re going to have for the rest of their lives.”[126] In September 2017, an Indiana warehouse worker was crushed to death.[127] At the time, Indiana officials were bidding on the company’s HQ2, and so worked with Amazon to convince state safety inspectors to not pursue the circumstances surrounding the worker’s death further.[128]

Amazon also contracts with multiple delivery services to take packages the last few miles between shipping hubs and customers’ doors. With high volume requirements for drivers—as much as a package delivered every two minutes – safety standards slipped.[129] Vans delivering Amazon packages were involved in hundreds of accidents, causing at least six deaths.[130] Drivers are poorly paid and barely trained, as Amazon’s contracted delivery companies often use vehicles that fall below the weight limit that triggers Department of Transportation oversight.

Because Amazon contracts with the delivery service companies, the corporation distanced itself from responsibility until increasing media scrutiny resulted in Amazon’s abruptly dropping several contracts with external delivery services.[131]

Amazon also requires all employees,[132] even temporary warehouse workers, to sign coercive contracts that include non-compete clauses.[133] These stipulations prevent employees from working either “directly or indirectly” for a competitor who offers goods or services that compete with those supported by the employee while at Amazon for up to 18 months following the employee’s departure from Amazon.

Amazon Leverages its Power to Avoid Taxes, Rake in Subsidies, and Acquire Government Contracts

Famously, Amazon paid nothing in federal taxes in 2018 and, over the last 20 years, has enjoyed nearly $3 billion in local and state subsidies.[134] Winning public subsidies and exploiting tax loopholes – which takes money, an army of corporate lawyers, and access to government officials that smaller businesses don’t have – have always been central to Amazon’s corporate strategy. Amazon has also acquired contracts to provide local and federal government agencies with goods and services through its marketplace.[135]

Amazon’s original tax break was in 1995. Bezos located Amazon in Seattle because at the time online sellers didn’t have to pay sales taxes except in the state where they were located, and Washington was a relatively small state. Since then, Amazon’s aggressive search for tax advantages has continued.

Most prominently, in September 2017, Amazon announced that it was seeking a location to place 50,000 jobs for its “second headquarters” and would accept sweeteners from interested municipalities. More than 238 localities responded, promising everything from Atlanta’s offer of an exclusive lounge for Amazon executives at Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport;[136] to the $8.5 billion in tax incentives and renovations offered by Montgomery County, Maryland;[137] to contracts allowing Amazon-related business to be restricted from freedom of information act requests.[138] One Georgia town even offered to rename itself “Amazon,” while New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo offered to rename a river after the company.[139]

Eventually, Amazon decided to split its new offices between a location in Long Island, New York, and another in Crystal City, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., for which it received a total of more than $2 billion in subsidies. After local protests in New York, Amazon decided to back away from locating its HQ2 building there. Then, in 2018, Amazon announced plans to locate in Manhattan despite having foregone tax breaks, confirming that Amazon was willing to locate in New York City regardless of financial incentives.[140]

Amazon also demanded that cities treat negotiations over HQ2 as trade secrets, resulting in several cities refusing to release details of what it offered the company even after they were already out of the running.[141] Several analysts have posited that the entire HQ2 search was about data collection on cities – as they were required to turn over demographic, wage, and land use data[142], and even prices at local Whole Foods stores[143] – during the bidding process, rather than genuine intent to ever put HQ2 anywhere other than the nation’s capital and the world capital of finance.

Amazon also often extracts tax incentives and other regulatory favors from communities in which it builds its warehouses, even though those warehouses are placed in strategic areas that align with both Prime subscribers and disposable income – in other words, Amazon builds where its customers are.[144] It also often makes those arrangements through shell companies, only announcing after the fact that Amazon will be the tenant of a warehouse, giving political opponents no opportunity to organize or lobby local lawmakers.[145] Amazon’s facilities are therefore subsidized in ways its competitors or brick and mortar stores are not.

But it’s not only taxes that subsidize Amazon’s monopoly. As explained earlier, it benefits from preferential pricing on shipping parcels through the United States Post Office, which includes shipping on Sundays when standard USPS mail is not delivered. The details of the contract between Amazon and USPS are not public. While many analysts say the arrangement is key to the USPS’s bottom line, it gives Amazon a leg up over shippers who can’t negotiate similar deals.

Amazon’s dominance of web services enables it to win still more subsidies from the government, entrenching its position as a preferred government contractor. For example, its dominance of cloud computing enabled it to win a $600 million CIA contract in 2013, which “effectively subsidized Amazon’s development of advanced capabilities needed to manage classified data, helping it become the only company that holds the Pentagon’s highest-level IT security certification, known as Impact Level 6.”[146] It became the front-runner, therefore, when the Pentagon looked for its own single-source cloud computing contract, worth $10 billion. It was only after political pressure that the Pentagon ended up giving the contract to Microsoft.[147]

A LEDGER OF HARMS: THE CONSEQUENCES OF AMAZON’S MONOPOLY

Thus far, this report has detailed how Amazon engages in anticompetitive behavior, tilting online commerce in its favor by using its size and market power to bully, surveil, and manipulate third-market sellers, producers, and even customers. These practices have knock-on effects beyond simply the economic harm endured by those who interact with Amazon directly or indirectly.

The list below is not exhaustive, but it shows why Amazon’s power is not merely about unfair commerce, but inhibits the creation of a fairer and more equitable society and ultimately harms American democracy.

Amazon increases economic inequality. Jess Bezos is the wealthiest man in the world, and some suggest he is on track to be the world’s first trillionaire.[148] By siphoning money from small businesses, squashing innovation, and creating low-wage, low-benefit jobs subsidized by public money, the company transfers a massive amount of wealth from communities, workers, and independent businesses and into Amazon’s own coffers.

Amazon depresses wages. A 2018 study by The Economist found that opening an Amazon fulfillment center in a community depresses warehouse wages. In counties without an Amazon center, warehouse workers earn an average of $45,000/year, versus $41,000/year in counties where an Amazon warehouse is located. The study also found that two and a half years after Amazon opens a fulfillment center, local warehouse wages fall by three percent.[149]

Amazon undermines local businesses. From 2000 to 2015, the economy lost more than 108,000 local, independent retail businesses, a drop of 40 percent when measured relative to population.[150] In a 2016 survey of more than 3,000 independent business owners, 70 percent noted that competition from Amazon was their biggest challenge.[151]

Amazon undermines local budgets. Small businesses that provide property and sales taxes, local jobs, and civic benefits are exchanged for Amazon warehouses that have high rates of injury and low wages, and are given discounts on their property tax payments as well.[152] Amazon alone is estimated to have reduced property tax revenue by $528 million in 2015.[153]

Amazon stifles innovation. Amazon’s aggressive posture towards competitors and the deep pockets of the corporation mean that startups are at risk from the “kill zone,” which means investors won’t put money behind ventures they think will compete with Amazon (or other big tech conglomerates) because those ventures will inevitably lose to Amazon or be acquired and closed down.

Amazon attempts to rig federal policy in its favor. Since 2014, the amount of money that Amazon spends on federal lobbying has jumped from $5 million in 2014 to nearly $15 million in 2018.[154] As of 2019, the corporation has more than 100 federal lobbyists, some of whom are former members of Congress or senior former White House officials.[155] It also funds interest groups that work to quell antitrust and other regulatory interventions.[156]

Amazon attempts to rig local policy in its favor. When city councilors in Seattle successfully passed a “head tax” on large businesses operating in the city, Amazon mobilized to have it repealed. It stopped construction on a new office building and threatened to leave the city if the tax stayed on the books. The council ultimately repealed the tax, saying that a months-long campaign against Amazon – which was trying to organize a ballot question against the tax – wasn’t worth the effort.[157]

During the 2018 election in Seattle, several progressive legislators made anti-Amazon messages a central part of their campaign.[158] In response, Amazon spent $1.5 million – a notable increase from the $25,000 the corporation spent in 2014 – to support pro-Amazon candidates. (In a repudiation of Amazon by Seattle voters, many of the progressives won despite Amazon’s spending in the race.[159]) It has also contributed to anti-tax campaigns and organizations in both Washington state and Oregon.[160]

Amazon exacerbates climate change. Amazon was slow to adopt climate change targets, then stalled out on them while entering into partnerships and providing cloud services to big fossil fuel companies: “Despite promising to make their operations more sustainable, Amazon’s massive cloud operation appears to once again be getting dirtier, powered by a growing share of fossil fuels. [Amazon Web Services] is then selling its fossil-fueled cloud to oil, gas, and coal companies, to help them better find and extract more fossil fuels. As of now, Amazon is burning the climate from both ends.”[161]

Amazon profits from technology that fosters discriminatory policing tactics. Amazon supplies police departments with both facial recognition software – which disproportionately misidentifies black people – and surveillance data from Ring that is often built on racial bias, sometimes without a requisite warrant. As one analyst put it, Amazon’s products enable law enforcement “to track and suppress those protesting and speaking out against racial injustice.”[162]

SOLUTIONS

Amazon’s interlocking harms stem from a variety of anti-competitive practices, as well as the ability to block the public, enforcers, and competitors from knowing about or litigating against those practices. Addressing a corporation as large, powerful, and complex as Amazon will require a variety of different tools, as well as structural solutions to eliminate conflicts of interest embedded in the corporation itself.

Each harm identified in this report has a legal underpinning. Changes required to reorient laws to eliminate these harms include the following recommendations.

Eliminate Self-Preferencing of Amazon’s Products on Platforms it Controls

Structural separation of platform and commerce. Through statute, antitrust remedy, or regulatory action, policymakers should prohibit platforms from selling competitive products on any marketplace whose rules they control. Such a structural separation could potentially impact Amazon Marketplace, Amazon Basics, Alexa, AWS, Fulfillment by Amazon, Ring, Kindle, Studios, Music, and Advertising.

Railroads, aerospace corporations, investment and commercial banks, television networks, bank holding companies, data processing/telecommunications and telephone systems have all been structurally separated for a variety of reasons, including preventing conflicts of interest.[163] Similarly, restoring essential facilities doctrine, which mandates non-discriminatory access to critical services, would be a complement to such structural separation, though on its own might be difficult to administer. [164]

One way to understand Amazon is that it is the combination of several lines of business put together. Amazon’s Marketplace is similar to eBay; its logistics arm is similar to United Parcel Service; its retail division is similar to Target; and Amazon Studios is similar to Netflix. Amazon discriminates in favor of its various internal divisions through self-preferencing and exploitation of bargaining power against customers and suppliers. instead of allowing these lines of business to make the most efficient deal with outside parties.

This bundling comes together most evidently in the Prime membership program. The cleanest, fastest, and most effective solution to address Amazon’s role in online commerce would be to simply split apart the different components that make up Prime – warehousing, packaging and delivery, movies and music, marketplace, and retail – likely through legislation.[165]

Prohibit Tying

Make tying by dominant platforms per se illegal. Amazon uses close connections between different parts of its business to extract more money from those who use its platforms. Third-party sellers who sell on Amazon Marketplace are given preferential treatment if they use Fulfillment by Amazon, even when FBA is more expensive than alternative shipping options. Structural separation would be a preferable way to address the problem, but making tying per se illegal for dominant platforms would provide an alternative path.

Restore Checks on Predatory Pricing

Strengthen predatory pricing law. Amazon’s below cost pricing strategy stems directly from the lack of rules around predatory pricing, which is the practice of selling products at a loss to gain market share. Right now, bringing a predatory pricing claim is impossible unless the plaintiff can prove below cost pricing for the purpose of acquiring market share, as well as the intent and ability to subsequently raise prices to ‘recoup’ losses. This ‘recoupment test’ was solidified in the Supreme Court cases Brooke Group Ltd. V. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp, as well as Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp, whose central claim was that “predatory pricing schemes are rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.”

Because Amazon is so large, and able to recoup money from any part of its business – not necessarily just on the product it underpriced – the case law is no longer sufficient.[166] Eliminating the recoupment test would restore predatory pricing doctrine.

Create stronger bureaucratic levers against below cost pricing. Another approach to prohibiting predatory pricing would be to restructure the FTC’s Bureau of Economics into the Bureau of Market Analysis to serve as an expert agency to manage predatory pricing complaints from small businesses. This could be modeled on the existing system of Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duty law.

Currently, the International Trade Administration (ITA) under the Department of Commerce takes complaints from domestic U.S. industries about foreign competitors who engage use unfair tactics, either dumping exports into U.S. markets at less than fair value or accepting government subsidies to unfairly produce below cost. Such anti-dumping or countervailing duty laws are similar to predatory pricing in that they are legal tools designed to stop anti-competitive subsidization or discriminatory pricing. The ITA investigates complaints and the International Trade Commission calculates harm. Having the FTC accept predatory pricing complaints and calculate whether corporations are selling products below fair market value or with cross-subsidization would allow small businesses to redress competitive harm.

Police Deceptive Search Results

Enforce against false and deceptive practices. Amazon’s advertising business relies on search displays that contravenes the FTC’s guidance on deceptively formatted search engines, as well as other possible areas where Amazon might use deceptive tools to acquire advertising revenue.[167] The FTC should enforce and potentially expand its guidance.

Protect Amazon’s Suppliers, Platform Dependents, and Customers

Add an abusiveness standard to the FTC’s Section 5 authority. Currently, the Federal Trade Commission has the authority to address unfair and deceptive practices and the authority to address unfair methods of competition. Since 1980, the FTC has used a definition of unfairness that significantly limits its ability to address problematic behavior by powerful entities. Adding an abusiveness standard, so that the FTC can halt unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices, or unfair or abusive methods of competition, would enable the Commission to more easily address practices in which Amazon coerces merchants or customers.

Enforce the Robinson-Patman Act. Currently, the Robinson-Patman Act lies dormant, despite its passage in 1936 to prevent the use of kickbacks and discriminatory pricing based on size for the purpose of monopolizing a market. The FTC should consider enforcing this law once again.

Restrict monopoly leveraging, refusals to deal, and/or restore essential facilities doctrine. Amazon’s ability to bully stakeholders relies on its ability to withhold its services, despite those services being critical rights of way. There are several paths to end these kinds of practices. Strengthening the law against refusals to deal, restoring ‘essential facilities’ doctrine requiring non-discriminatory access to markets/vital resources, or leveraging monopoly power from one market into another, all of which have been eroded or undermined by case law, would limit Amazon’s ability to withhold vital services to competitors. [168]

Make it easier to bring class action antitrust lawsuits. Amazon’s various coercive tactics receive little pushback in part due to the difficulty in bringing class action lawsuits against the corporation. Eliminating arbitration agreements that prohibit class action antitrust suits, reducing the legal burden required to certify classes, and imposing anti-retaliation provisions would enable litigants to band together and prohibit coercive arrangements.[169]

Strengthen investor disclosures with lines of business requirements. Amazon’s ability to withhold financial information around Prime, Advertising, FBA, and private labels are key to preventing enforcers, customers, and competitors from seeing how the corporation might be engaging in unfair practices. (The Securities and Exchange Commission has asked Amazon for financial information around Prime, but Amazon refused to offer it.) Lawmakers or regulators should expand disclosure requirements so that large corporations, especially those who operate as infrastructure-like platforms, must explain in detail their different operating divisions, including costs, revenues, and profits for lines of business.

Protect Businesses from Amazon’s Surveillance and Copycatting

Add privacy protections for business data. Currently, businesses dependent on platforms have no inherent privacy rights over their vital business data and must set those rights through contractual bargaining. Given the asymmetry of power between Amazon and any merchant or platform dependent business, statutory guarantees prohibiting the abuse of proprietary business data collected as an incidental act necessitated by use of the platform would redress Amazon’s ability to surveil its merchants. One potential model is the Customer Proprietary Network Information, rules that prohibited telecommunications networks from using data required for interconnecting customers for marketing purposes.[170]

Purpose-limitation of data. Amazon should be prohibited from using data collected on one platform to target consumers on any other platform. As Brave’s Chief Policy & Industry Relations Officer Johnny Ryan has noted, such a limitation is contained within the European privacy law Article 5(1)(b) known as the General Data Protection Regulation.[171]

Prevent Amazon from Weaponizing Counterfeit Products

Harmonize liability standards for retailers and platforms. Courts have found that electronic marketplaces are not liable for products sold by third party merchants on their platforms. State or Federal legislation to make such marketplaces liable, such as California’s AB-3262 or the SHOP SAFE Act of 2020 introduced in Congress, would address this problem.[172]

Limiting Amazon’s Acquisitions

Restrict or ban acquisitions by dominant platforms. Amazon buys competitors as well as corporations that offer key inputs that other industry participants might need. Ending Amazon’s acquisition spree would limit the corporation’s ability to grow as aggressively. In addition, currently venture capitalists have an incentive against financing competition to Amazon for fear of being unable to sell unrelated portfolio companies to the retail giant. Banning Amazon from acquiring competitors would force a more even playing field and trigger more investment and innovation.

Protect Amazon’s Workers from Abuse and Exploitation

Make noncompete clauses illegal. Amazon uses noncompete clauses to prevent workers from seeking other jobs, depressing their bargaining power. These clauses should be banned, either by the Federal Trade Commission, state legislatures, or Congress. The House of Representatives has passed legislation, the FAIR Act, that would ban coercive arbitration between employers and workers. A few states, like California, prohibit judicial enforcement of non-compete clauses, but a national ban is needed.

Stronger labor laws and safety standards. Laws at a state or federal level that make it easier to form unions would allow workers to collectively bargain for wages, benefits, and safety equipment. Such laws include ending right-to-work provisions at a state level, or changes at a federal level that would make it easier for workers to form unions and bargain for contracts. In addition, more authority and funding for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration would elevate safety standards for Amazon employees more generally.

Stop Amazon’s Public Subsidization