Capital One-Discover: A Competition Policy and Regulatory Deep Dive

By Shahid Naeem

This report is a competition policy and regulatory analysis of Capital One’s proposed acquisition of Discover. This deal would (1) allow Capital One to increase interchange revenue by increasing fees on merchants, (2) increase Capital One’s asset base so it gains access to a de facto government backstop, and (3) fortify Capital One’s market power in the credit card industry. We believe this deal is likely to face serious regulatory headwinds and is unlikely to be consummated.

Part I: Parties, Markets, and Acquisition

Capital One, a major U.S. bank and top credit card issuer, has announced its intention to purchase financial services company Discover in a $35.3 billion all-stock deal. As banks, both firms operate primarily online: Capital One has a relative handful of bank branches — just 250 nationwide — and Discover’s sole physical branch is located in Delaware. Capital One is America’s ninth-largest bank, holding around $475 billion in total assets,[1] and is the nation’s largest auto lender.[2] Discover is the 27th-largest U.S. bank, holding $150 billion in assets.[3] Capital One and Discover are the fourth-largest and sixth-largest U.S. credit card issuers, respectively.[4]

Relevant Markets

The key markets of this transaction are banking, credit cards, and payment networks.

Banking: The United States banking system is characterized by tiers: a handful of large banks whose size and complexity carry an implicit government backing, midsized banks that play key roles in regional commerce, and several thousand smaller banks focused on community lending.

Credit card issuers: Credit cards are a key product and submarket in banking. They are nearly ubiquitous: 82% of adults carry one, and credit card debt is the most common form of debt in the U.S., recently cresting $1 trillion.[5] Bank credit card operations consistently generate greater revenue than other bank activities, at about 4.3 times the banking industry’s average return on assets.[6] Banks that issue credit cards earn revenue primarily through charging cardholders interest on outstanding balances; banks also receive a percentage of the interchange fees charged by payment networks to process transactions.

Payment networks: Payment networks are the rails on which all card transactions travel. Payment networks transform credit and debit cards from strips of plastic into vital tools of commerce. Banks that issue credit and debit cards rely on payment networks to connect the cardholder and issuing bank to the merchants and their banks, allowing transactions to be authorized and settled in real time. Payment networks earn revenue by charging businesses interchange fees, or “swipe fees,” for the use of their networks, sharing a cut of that revenue with the card issuer’s bank.

Payment networks are a high-margin industry, with the two largest payment networks, Visa and Mastercard, consistently at the top of the S&P 500 index’s average net profit margin measurements — around five times those of the average indexed firm.[7] Beyond Visa and Mastercard, there are only two other payment networks: American Express and Discover. High barriers to entry and network effects have prevented the formation of new competitors: Discover, the last major network to arrive, came online in 1984.

“Born Analytical”: Capital One’s Business Model

Capital One was “born analytical.”[8] The firm combines cutting-edge data science with an industry-leading ability to identify high-margin customers — in the credit card industry, these are cardholders who do not pay their credit card bills and revolve monthly balances subject to interest and fees. An innovator since its emergence in the payments industry in 1994, the firm “has built an entire business on the savvy use of information technology,”[9] and is routinely recognized as a “game-changing technology” leader[10] whose “unrelenting focus” on data analytics has underpinned “sector-leading growth.”[11]

According to McKinsey, Capital One is one of the best-practice examples in the industry of “Customer Value Maximization,” able to tailor higher-yield products to tens of thousands of different customer segments.[12] Sifting through large data sets, the firm runs 80,000 data experiments per year, able to test different combinations of credit card features, including interest rates, payment options, and rewards, on different customer profiles to optimize profitability.[13] This allows Capital One to identify lower-credit, higher-risk cardholders who are more likely to miss payments and revolve a balance.[14] The interest charged to cardholders on their balances is the primary source of revenue for Capital One, at more than half of the firm’s total net revenue.[15] Capital One is also an industry leader in pricing, with interest rates above 30% that maximize return on cardholder balances.[16]

Capital One’s data operations also enable it to be a dominant player in credit card lending to Americans with poor credit. In this higher-risk “subprime” segment, where banks lend to Americans with FICO scores below 660, the sophisticated use of data to minimize losses can make or break success. Despite being the fourth-largest credit card lender overall, Capital One is America’s largest subprime credit card lender, with a higher percentage of its total credit lending in the subprime segment compared to rivals like JPMorgan Chase, Citi, or Discover.

As a result, Capital One cardholders are more likely to revolve monthly balances.[17] The firm exhibits higher default rates and 30-day delinquency rates than JPMorgan, Citi, Discover, or American Express,[18] as well as the second-highest 30-to-89-day delinquency rate as a percentage of its total loans, behind only Discover.[19]

Transaction Strategy: “Scale” to “Grail”

While absorbing Discover represents an opportunity to bolster Capital One’s banking footprint and take the lead market position among U.S. credit card issuers, the heart of the transaction is the firm’s acquisition of the Discover payment network. “The Discover payment network positions Capital One as a more diversified, vertically integrated global payments platform,” said Capital One CEO Richard Fairbank during the firm’s call introducing the merger.[20] Accordingly, on that call, the word “issue” or “issuer” was mentioned 11 times; variations of the word “bank” or “banking” 39 times; and “network” was mentioned 110.[21]

Capital One aims to accomplish the following with this transaction:

Banking: Bigger Is Better. Capital One aims to become a bigger bank. Slide 17 of its investor presentation explains: “We will increase our scale to compete with the nation’s largest banks.”[22] The transaction would do just that, making Capital One the sixth-largest U.S. bank by assets, at around $625 billion.[23] Capital One would absorb Discover’s digital-first nationwide consumer banking business, adding $84 billion in retail deposits to its existing $346 billion in deposits, as well as its mortgages, personal loans, and other banking products.[24]

Credit Cards: Scale Matters. Capital One aims to become a bigger credit card issuer. The firm has determined that the credit card industry is driven by scale. “The reason there’s been more consolidation is just the underlying, just incredible power and physics of scale,” Fairbank said on the investor call, observing that the credit card industry is even “more scale-driven than a lot of other parts of banking” like commercial banking and small business lending, which “tend to be more fragmented across many banks.” Buying Discover’s credit card issuer business, he said, is “increasing our scale where it matters.”[25]

Capital One’s acquisition would make the firm the largest U.S. credit card lender: By card balance, Capital One would own around 24% of all outstanding U.S. credit card loans, a total of around $257 billion.[26] The deal would add 75 million Discover credit cards in circulation to Capital One’s substantial base of 106 million.[27] Through the Discover network, Capital One would be able to reach around 305 million cardholders worldwide.[28]

Source: Bloomberg

Payment Networks: The Holy Grail. Networks aren’t just valuable — they’re rare.[29] “We all kind of revel in the fact that a network is a very, very rare asset,” Fairbank said, adding, “There are very few of them. I don’t think people are going to be building any of these anytime soon because it’s such a chicken-and-egg problem to ever get one started.” As he acknowledged, networks are rare because they are hard to start, but once they are operational, their scale and size of user base is their value, a phenomenon known as the network effect. “There’s a reason it’s called a network,” Fairbank said. “Because it has network effects associated with it.”[30]

For Capital One, the Discover network is the crux of the acquisition. Acquiring a payment network strengthens its market position in banking among credit card issuers, saving costs by eliminating reliance on Visa and Mastercard’s high-priced payment networks. Owning networks in both credit and debit payment ecosystems also allows Capital One to go from being a toll-payer on the payment network highway to a toll-collector. While Capital One’s estimated $1.2 billion yearly of “network synergy opportunities” assumes its network pricing stays static, the transaction unlocks compelling opportunities to flex network pricing power to increase revenue.[31]

Becoming an issuer-network enables Capital One to circumvent the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act’s Durbin Amendment, a law designed to moderate the transaction costs associated with debit cards for businesses. The law caps the debit card interchange prices set by networks and requires debit card issuers to offer multiple competing networks on their cards to incentivize price competition.[32]

Avoiding the Durbin Amendment is a core part of the transaction: Discover’s PULSE debit network has a higher purchase volume than its credit counterpart,[33] and “the significant majority of the modeled network synergies are on the debit side,” according to Capital One’s Fairbank, who emphasized that the Durbin debit rules “explicitly exclude networks like Discover and American Express.”[34] Accordingly, Capital One plans to move its entire debit card business from the Mastercard network to the Discover network almost immediately.[35] Compounded by its expanded retail bank account portfolio, Capital One would enjoy heightened debit network pricing power — giving it an “unfair advantage” over its rivals, according to JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon.[36]

In contrast with its clearly stated desire to shift its entire debit volume from Mastercard to Discover’s debit network, Capital One is more opaque about its plans for credit. The firm says it aims to, “over time,” convert “a growing portion” of “selected Capital One credit portfolios” to the Discover network.[37] Of its stated goal to move $175 billion in additional spending volume to the Discover network by the year 2027, it is unclear what portion Capital One projects as credit card spending.

Part II: Merger Environment and Regulatory Risk

This transaction must pass a merger review process mandated by the Bank Merger Act and Bank Holding Company Act, which will be carried out by regulators at the OCC and Federal Reserve. Bank merger review involves a multi-factor assessment of the transaction’s effect on competition, risks to financial stability, and impact on the public interest, as well as a review of the condition of the banks’ finances, management, and future prospects, and the banks’ record combating money laundering.[38]

The Justice Department Antitrust Division is also involved in the banking agencies’ review. The banking statutes require the Division to provide a “competitive factors report” to the banking agencies with its evaluation of the merger’s effect on competition. The Justice Department also retains the authority to sue to block mergers approved by bank regulators, doing so most famously in United States v. Philadelphia National Bank.[39]

Running the Gauntlet: Regulatory and Political Environment

The transaction faces a challenging regulatory environment. Capital One appears to have designed the deal accordingly: A $1.38 billion breakup fee applies in the event of a rival bid emerging but will not be owed if regulators block the deal, suggesting the firm may have less confidence in consummating the deal than it has projected publicly.[40]

The Biden administration has ratcheted up U.S. antitrust enforcement, and banking has been no exception. Responding to what was deemed an “increasingly permissive” environment for bank mergers,[41] a July 2021 presidential executive order on competition aimed to tighten merger policy in the sector, tasking bank regulators at the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) with strengthening bank merger oversight to “guard against excessive market power.”[42] Under Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter, the Justice Department Antitrust Division has rejected prior divestiture-focused approaches in the sector and signaled a return to its statutory role as an antitrust enforcer in banking.[43]

Beyond the Antitrust Division’s standing authority in bank mergers, the Justice Department has traditionally enforced antitrust law in payment systems, notably suing to block Visa’s acquisition of payments platform Plaid in 2021.[44] The platform and network elements of Capital One’s acquisition of Discover, coupled with the Division’s renewed focus on bank competition, likely forecast heavy Antitrust Division involvement in the merger review process.

The banking sector and its regulators are also under heightened political scrutiny after a series of regional bank failures in 2023 raised financial stability concerns, exposed flaws in bank supervisory programs, and led to government-assisted emergency acquisitions that deepened critics’ concerns about industry consolidation.[45]

In January 2024, the OCC released a policy statement intended to increase the transparency of its merger review process, outlining the principles the agency uses in each element of its Bank Merger Act review.[46] The policy statement identified 13 indicators, all of which are generally featured by merger applications eligible for approval. Of these, Capital One’s acquisition of Discover may conflict with five, each discussed below, apart from indicator 12, whose “no significant legal or policy issue” indicator may be infringed by the transaction’s interaction with the Durbin Amendment.[47]

The transaction is also highly politicized. In February, Senator Elizabeth Warren and a dozen other Democratic lawmakers urged the Federal Reserve and OCC to block it, calling the deal’s regulatory review in a letter “one of the most important tests of [the Biden administration’s] efforts to prevent harmful bank consolidation.”[48] In a separate letter, Representative Maxine Waters and 15 Democrats identified “myriad issues” with the deal, calling for a revamp of bank regulators’ merger review policy.[49] And in a letter to the Justice Department, Republican Senator Josh Hawley urged antitrust enforcers to challenge the deal, calling it “destructive corporate consolidation.”[50]

Does This Acquisition Violate Antitrust Laws?

In 2023, the Justice Department, along with the Federal Trade Commission, released a document outlining how the agency enforces antitrust law when reviewing mergers and acquisitions across the economy.[51] The 2023 merger guidelines will shape how the Justice Department composes its competitive factors report to the Federal Reserve and OCC as part of the Bank Merger Act review process, as well as any possible legal challenge to a banking agency-approved transaction.

Capital One’s acquisition is likely to draw scrutiny across several guidelines. The transaction takes place in concentrated markets (Guideline 1), which may be “trending towards consolidation” (Guideline 7). The acquisition may threaten to eliminate substantial competition between firms (Guideline 2), and it involves a multi-sided platform whose control may entrench the acquiring firm’s market power in an adjacent market position (Guideline 9). The guidelines also note that antitrust enforcers “have in the past encountered mergers that lessen competition through mechanisms not covered” in each guideline, offering as an example, “[a] merger that would enable firms to avoid a regulatory constraint because that constraint was applicable to only one of the merging firms.”[52] Capital One’s stated intent to acquire Discover’s Durbin debit rule exemption will likely be scrutinized along these lines.

Market Concentration and Trends Toward Consolidation

Per Guideline 1, mergers that “significantly increase concentration in a highly concentrated market” are “presumptively illegal” because creating or further consolidating a highly concentrated market “may substantially lessen competition,” in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act.[53] A market’s “trend towards consolidation,” as outlined by Guideline 7, is also a relevant factor in determining a merger’s effects on competition.

Each of the three markets implicated in the transaction is particularly concentrated:

Banking: The U.S. banking sector is undergoing both long-term and contemporary trends towards consolidation. Today, the largest six banks control more assets than all others combined ($13.6 trillion),[54] while the share of the nation’s bank deposits held by the largest financial institutions has increased. Since 1995, when the largest four banks controlled under 10% of the nation’s deposits, their share has quadrupled, with the four biggest banks owning 36% of U.S. deposits in 2020.[55] The share of total assets held by smaller banks with total assets under $1 billion has decreased from 25% in 1994 to 6% in 2019.[56]

Banking is also experiencing a more recent trend towards consolidation, outlined by Guideline 7 as a relevant factor in determining a merger’s effects on competition.[57] After Dodd-Frank rollbacks in 2018, a series of high-profile mergers between large banks took place. Through 2020 and 2021, U.S. Bank and Union Bank merged to become the fifth-largest bank, as did SunTrust and BB&T, PNC and BBVA, BMO and Bank of the West, M&T-People’s United, Huntington-TCF, and First Citizens-CIT, creating the sixth, seventh, 15th, 17th, 25th, and 38th largest U.S. banks respectively.[58]

Credit Card Issuers: The credit card market is similarly consolidated. In 2007, the former general counsel of Citigroup’s U.S. credit card businesses described the industry as “a cartel.”[59] Ten of the largest 4,000 banks that issue credit cards control 83% of credit card lending, with the five largest issuers owning two thirds of all outstanding balances.[60] Regulators have observed “high levels of concentration” in the consumer credit card market and “evidence of practices that inhibit consumers’ ability to find alternatives to expensive credit card products.”[61]

Consolidation has led to high interest rates and fees. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) research found that larger credit card issuers charge Americans significantly higher interest rates — as much as eight to 10 APR points higher — than smaller issuers, hitting record-high APR margins in 2023.[62] In total, Americans paid issuers a record $130 billion in fees and interest in 2022.[63] The credit card issuing market has also trended toward consolidation: The share of total credit card loans held by the top 10 issuers has more than doubled, from 40% in 1988 to today, resulting in a market characterized by “economies of scale that favor large issuers.”[64]

Payment Networks: Payment networks are perhaps the most consolidated of the deal’s relevant markets. “Can the Visa-Mastercard duopoly be broken?” asked a 2022 headline published by free-market champion The Economist, highlighting the firms’ combined 80% market share and the U.S.’s “heftiest interchange fees of any major economy.”[65] “Visa-Mastercard payments duopoly has staying power,” a 2021 Reuters headline affirmed, observing that despite the rise of new financial technologies, “the duopoly is stronger than it appears.”[66] A 2023 Barron’s feature underscored lack of competition in the market, noting that Visa’s and Mastercard’s “fat profit margins of 52% and 44%, respectively, are maintained because the merchants that pay the fees have little choice,” remarking that investors “love the stocks,” because of “the companies’ seemingly unbreakable stranglehold on electronic payments at the register.”[67]

The rest of the market is represented by American Express and Discover, whose market shares represent around 20% and 4% respectively.[68]

Pricing

Antitrust enforcers will also evaluate whether the transaction will give Capital One the ability and incentive to raise prices in any of the related markets.

Banking: Enforcers are likely to be aware of empirical and historical evidence outlining how mergers increase banks’ incentive and ability to raise costs of credit for consumers and businesses, increase fees, and lower interest rates paid to depositors.[69]

Credit Card Issuers: Analysis of card pricing data shows that today Capital One exerts higher interest rate pricing power than Discover within the same FICO score ranges. For cards in the “Good Credit” FICO score range of 620-719, Capital One charges three APR percentage points higher than Discover, while for “Great Credit” (FICO 720 or above), the firm charges four APR percentage points more.[70] If Capital One were to raise Discover APRs offered to new accountholders to match its own, consumers in the market would lose access to lower-APR cards; similarly, if the firm repriced existing Discover cardholder rates to match its own, prices for existing Discover cardholders would rise.

Payment Networks: Capital One’s acquisition of the Discover network is likely to be an area of interest for enforcers examining the combined firm’s pricing power. In combining its credit card business with Discover’s network, Capital One will gain the ability and incentive to raise interchange fees for merchants, who are likely to lack any real ability to turn away the nation’s largest issuer. The current dynamics of interchange fees discourage price competition, sustaining long-term increases in fees despite lower costs for networks over time. American Express, the only other vertically integrated issuer-network, charges merchants the industry’s highest interchange fees to access its customer base.[71] Visa and Mastercard use their market position to raise interchange fees regularly, most recently in August 2023.[72] In 2012, U.S. businesses paid $32.73 billion in interchange fees, representing 1.4% of total U.S. credit card spending volume; in 2021, businesses paid $93.2 billion, or 2% of total credit volume.[73]

Discover’s debit networks may raise pricing power concerns, particularly given the network’s exemption from both interchange fee caps and routing requirements. Like its credit network acquisition, its status as a major issuer and owner of a debit network may give the firm the ability and incentive to raise interchange fee costs. One financial services analyst estimated that Capital One could exercise its ability to hike debit interchange fees to increase earnings by $800 million yearly, a cost that would be borne by American business and consumers.[74]

Head-to-Head Competition

Antitrust enforcers will also examine head-to-head competition between Capital One and Discover in relevant markets. Because a merger between competitors necessarily eliminates competition, “If evidence demonstrates substantial competition between the merging parties prior to the merger, that ordinarily suggests that the merger may substantially lessen competition.”[75]

Enforcers are also likely to examine competition in submarkets.[76] The expansion of Capital One’s leading position in subprime credit card lending (identified by cardholder FICO scores below 660) by adding Discover’s portfolio in the same category may draw scrutiny. Capital One has shown the ability to more profitably underwrite the higher-risk segment at a greater percentage of its total card loans issued than rivals: 32% of its credit card lending is in the subprime segment, a higher proportion than rivals like JPMorgan Chase (14%), Citigroup (20%), or Discover (20%).[77]

With the addition of Discover’s $20 billion in subprime card loans, Capital One would more than double those of JPMorgan Chase ($30 billion) and Citigroup ($33 billion), the next-largest major bank subprime lenders.[78] Preliminary analysis of regulatory filings suggests the deal could increase the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI, a measure of market concentration used by antitrust enforcers) of the subprime credit card market to levels that would classify the transaction as presumptively illegal under current enforcement standards.[79]

Capital One and Discover also compete outside the subprime card loan segment. While the former has drawn attention for its presence in subprime card lending, both do the majority of their lending above the 660 FICO score threshold, territory that covers cardholders with near-prime, prime, and super-prime credit.[80] According to several industry analysts, advancing Capital One’s strong share in the near-prime segment — a segment it has “historically specialized in,” characterized by profitable balance revolvers — could draw regulatory scrutiny.[81]

Firm data on segment-specific lending market share is proprietary but will be accessed by enforcers in a merger case. However, an analysis of Mintel marketing data suggests that Capital One and Discover compete for the same customers. For example, Capital One and Discover are the only two major banks competing for near-prime credit customers via a major customer acquisition channel: direct mail marketing.[82] But Capital One and Discover are also two of the top four banks targeting prime credit customers by total direct mail volume, and both firms target subprime, near-prime, and prime customers at a higher share of their direct mail offers than No. 1 issuer JPMorgan Chase, suggesting they compete closely across FICO bands.[83]

Beyond market share, enforcers may also use analysis of existing competition between the merging firms to demonstrate that a deal is anti-competitive. Whether Capital One and Discover monitor each other’s products, pricing, marketing, or innovation plans — and whether they react to each other by changing their own products or services — can provide evidence of competition between the merging firms, as well as whether customers are willing to switch between the rival firms’ products.[84]

“Merge to Compete” in Payment Networks

Capital One has framed its acquisition as a transaction that will increase competition in the payments industry. This position may struggle under scrutiny if regulators or courts find either a lack of supporting evidence or that legal precedent negates its relevance.

First, a merger’s alleged pro-competitive benefits are often legally irrelevant: As acknowledged in 2023 by federal Judge William Young in his ruling in favor of the Justice Department’s challenge to JetBlue’s acquisition of Spirit Airlines, the merge-to-compete argument or so-called “efficiencies defense” contravenes Supreme Court precedent and cannot be used as justification for an otherwise illegal merger.[85]

Second, enforcers and courts may find the factual basis of the deal’s pro-competitive benefits unconvincing:

Discover’s Static Market Share: Discover has been unable to increase its payment network market share over time. In 2022, Discover, the smallest of the four payment networks, processed $211 billion in card transactions, giving it around a 2% market share by total card transaction volume, behind American Express (11%), Mastercard (25%), and Visa (60%).[86] In 2008, Discover’s market share by transaction volume stood at about 3%, with American Express at 14% and the remaining 83% Visa and Mastercard.[87] In order for Discover’s market share to increase, the merger would have to add significant purchase volume or somehow retool Discover’s methods of competition in a way it has not previously managed.

Unclear Path Toward Competition: Capital One has provided no insight into how it will make the Discover network a viable payments network competitor, either by adding competitively significant purchase volume or retooling Discover’s methods of competition to gain market share. The current information landscape suggests both are unlikely.

Capital One believes an “injection of volume and investment in the network will help Discover be competitive with the leading networks.”[88] But at a March 2024 conference, a senior executive said the firm will shift a “relatively small portion” of credit volume to the Discover network within three years, part of a long-term process that will happen in “small steps.”[89] This suggests the firm does not intend to significantly increase credit volume for some time. In fact, Capital One’s hesitancy toward increasing Discover network credit volume has convinced some analysts it may not plan to. In a Bloomberg TV appearance, one KBW analyst projected that the merged firm is “probably going to keep a substantial amount of their credit card volumes still on the Visa and Mastercard networks.”[90]

Even if Capital One met its $175 billion goal of added purchase volume to the Discover network solely via credit transactions – for example, by migrating Visa/Mastercard-networked credit cards – the shift would cut into the Visa-Mastercard market share just .033%, or one-third of 1%.[91] In a research note to clients, one investment bank analyst projected that by 2027, the transaction will eat into Mastercard’s revenue by about $636 million annually, equivalent to a 2% drop in revenue, while Visa would lose around $134 million annually, a decline of less than 1%.[92]

Beyond the numbers, a viable path toward adding meaningful Discover network volume to increase competition among networks is unclear. Discover cards are already accepted at 99% of U.S. merchants that take credit cards, leaving little room to add volume by increasing merchant acceptance domestically.[93] And almost all cards on the Discover network are issued by Discover, leaving little room to further saturate its own network.

Likewise, Capital One has outlined no plans to open the Discover network to other issuers or to otherwise increase the number of issuing banks on its network, either of which could increase network purchase volume and could lead to an increase in its market share. Increasing transaction volume abroad could be an option — Capital One raised the possibility on its investor call — but many overseas payments network markets limit interchange fees well below U.S. rates, making it a costly project. Regardless, U.S. antitrust enforcers will not use a merger’s alleged pro-competitive effects abroad to justify consolidation at home.

Multi-Sided Platforms

Even if Capital One is able to persuasively show that it will expand Discover’s market share in payment networks, enforcers’ analysis will be attuned to how Discover’s network impacts competition in the transaction’s relevant markets. As stated in the 2023 Merger Guidelines, mergers involving “multi-sided platforms … can threaten competition, even when a platform merges with a firm that is neither a direct competitor nor in a traditional vertical relationship with the platform.”[94]

Antitrust Division head Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter recently highlighted platform transactions as a point of emphasis for the Justice Department in merger review. Platforms “often defy simple horizontal competition and vertical distribution relationships,” he wrote in a July 2023 Journal of Antitrust Enforcement article, both “heighten[ing] the risk that a platform can entrench its power” and enabling platform owners to use their positions “to pick winners and losers in adjacent markets.”[95]

Bank Merger Act Review: Does This Acquisition Violate Federal Bank Merger Laws?

Regulators at the Federal Reserve and OCC are required to review transactions for approval using the framework set forth in the Bank Merger Act and the Bank Holding Company Act. Beyond the transaction’s effect on competition, they will evaluate its risks to financial stability and impact on the public interest, as well as review the condition of the bank’s finances, management, and future prospects, and the banks’ record combating money laundering. Capital One’s acquisition of Discover may draw scrutiny across each of the five components of statutory review.

Financial Stability and Systemic Risk

After the 2008 financial crisis, Congress amended the federal bank merger statutes to require regulators to determine a merger’s “risk to the stability of the United States banking or financial system.”[96]

Size and Complexity: Capital One’s acquisition of Discover would significantly increase its size. At $625 billion in assets, the firm would eclipse Goldman Sachs ($521 billion) in size and nearly double that of Bank of New York Mellon, both global systemically important bank (GSIB)-designated firms.[97] The acquisition also infringes on an OCC policy statement indicator, which identifies “mergers resulting in an institution with total assets less than $50 billion” as consistent with approval.[98] This transaction would create an institution around 13 times that size.

The OCC also highlighted that the agency’s financial stability analysis will consider material increases in “the extent to which the combining institutions contribute to the complexity of the financial system,” and whether it would “increase the relative degree of difficulty of resolving or winding up the resulting institution’s business in the event of failure or insolvency.”[99] Regulators may decide that Capital One’s purchase of Discover, particularly the network element of the transaction, does both.[100]

Regulatory and Supervisory Flaws: Recent events may amplify pressure on banking regulators’ assessment of the transaction’s impacts on financial stability. Banking agencies have come under pressure for what critics perceive as an insufficiently rigorous application of financial stability analysis in merger review,[101] a process characterized by a former Federal Reserve governor as one that “remains analytically underdeveloped” and is “being applied in a haphazard fashion.”[102]

Recent events have brought these concerns to the forefront of banking policy. The Federal Reserve’s 2021 determination that Silicon Valley Bank would not a “pose significant risk to the financial system in the event of financial distress” may still be fresh;[103] likewise, the FDIC’s subsequent invocation of the systemic risk exception to resolve the failures of SVB and Signature Bank — which were around one-third and one-sixth the size of a proposed Capital One-Discover, respectively — may increase regulators’ hesitancy to ignore financial stability risk.[104]

Supervisory struggles may also impact bank regulators’ willingness to approve a tie-up among the largest U.S. banks. Following the collapse of SVB, the Fed’s supervisory wing took part of the blame: “Federal Reserve supervisors failed to take forceful enough action,” wrote Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr in a postmortem report.[105] These concerns are ongoing: A March 2024 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that the Federal Reserve and FDIC have not yet fully addressed the agencies’ bank supervision deficiencies.[106]

Regulators will also consider whether approving a merger of this size is desirable from a resolution standpoint. Whether existing large bank resolution plans are realistic is a point hotly debated by top regulators and have been described as “a fairy tale” by FDIC board member and CFPB Director Rohit Chopra.[107] In a report outlining the biggest challenges facing the agency, the FDIC — responsible for resolving bank failures — stated that “key areas of concern” for the agency included properly detecting risk and preparedness to resolve bank failures in an orderly fashion.[108] The FDIC noted in its report that staffing was also a major issue: In five years, the FDIC lost more employees than it hired, including 20% of employees who handle bank failures.

Financial/Managerial Resources and Future Prospects

The Bank Merger Act requires that bank regulators consider the managerial resources, financial resources, and future prospects of the combining and the resulting institutions. This includes an assessment of the firms’ supervisory record, aimed at ensuring “safe and sound operations of the resulting institution.”[109]

Future Prospects: Asset Concentration: A merged Capital One-Discover would have a key vulnerability that may impact the future prospects of the merged firm: asset concentration.[110] The combination of two large financial institutions with asset concentration in credit cards, as well as other consumer lending products similarly sensitive to economic stress like auto loans, could leave the combined firm vulnerable to an economic downturn. According to 2023 year-end regulatory filings, $121 billion of Capital One’s $440 billion in assets lie in credit card loans, a ratio of 27.5%, while nearly $100 billion of Discover’s $147 billion in assets do (68%), leaving the combined firm with nearly 40% of its total assets concentrated in credit card loans alone.[111]

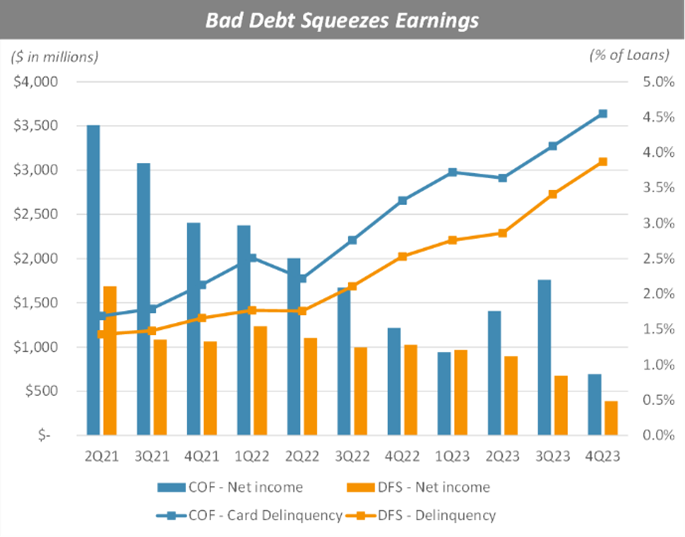

Source: The Last Bear Standing

Bank regulators are well aware of both Capital One’s and Discover’s asset concentration risk. Both banks perform worse than peers on Federal Reserve stress tests,[112] which include simulated surges in credit card defaults, with Capital One suffering a recent stress test’s largest total loan loss.[113] A February 2024 New York Federal Reserve report warned that credit card delinquencies are on the upswing,[114] with both Capital One and Discover experiencing recent surges in charge-offs and delinquencies, impacting earnings.[115] Today, Capital One and Discover carry the highest level of subprime credit exposure among all large U.S. banks.[116]

Recent casualties of asset concentration include Silicon Valley Bank, whose reliance on uninsured sector-specific deposits led to its failure, and Silvergate, whose exposure to cryptocurrency volatility caused its demise.[117] More recently, regulators approved New York Community Bank’s acquisitions of both Flagstar Bank and a significant chunk of Signature Bank despite NYCB’s overconcentration in commercial real estate (CRE) loans. From January through March 2024, the bank has flirted with collapse.[118]

Finances and Management: Both firms have had compliance failings that have led to enforcement actions in recent years. In particular, Discover’s management and regulatory compliance failings have been highly publicized. The resignation of Discover’s CEO in August 2023 for self-admitted “deficiencies” in corporate governance and risk management came just one month after the firm disclosed to regulators that it improperly overcharged merchants as much as $365 million in interchange fees.[119] Around the same time, Discover’s CFO acknowledged publicly that there were “too many” regulatory failures mounting.[120] Today, Discover is facing several investor lawsuits alleging senior leaders misled investors about the firm’s compliance programs.[121]

Discover was the target of CFPB consent orders in both 2015 and 2020 related to its loan servicing practices, which the CFPB found violated the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010, the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, and the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation E.[122] More recently, in October 2023, Discover was the target of an FDIC consent order for “unsafe or unsound banking practices,” stemming from flaws in the bank’s compliance programs.[123]

Capital One’s legal and compliance track record may also attract concern from bank regulators. The firm’s $9 billion acquisition of online bank ING Direct in 2012, billed as “transformational” by the firm,[124] was approved by the Federal Reserve on the condition that Capital One upgrade its risk management approach after a number of commenters complained that the firm was violating state and federal consumer protection law.[125] Despite this, the firm has had a range of compliance issues in the years since. Most recently, in 2021, Capital One was the subject of a Treasury Department enforcement action for violating the Bank Secrecy Act, a federal anti-money laundering statute.[126] A 2019 hack of Capital One’s data systems compromised 100 million Americans, leading to an OCC consent order and $80 million fine for the firm’s failure to properly manage IT risk.[127] These enforcement actions, alongside a 2019 Justice Department settlement for discriminatory recruiting practices,[128] could lead the OCC to trigger restrictions on the bank’s growth, per 2023 “persistent weaknesses” enforcement manual revisions.[129] Additionally, in its January 2024 policy statement, the OCC identified merger applications where “the acquirer has no open formal or informal enforcement actions” as consistent with approval.[130]

Public Interest

During merger review, bank regulators are required by statute to take into consideration “the convenience and needs of the community to be served.”[131] Commonly understood as a simple test of the banks’ Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) ratings, Congress designed the Bank Merger Act’s public interest assessment to be a wider-ranging review, one described by the Supreme Court as “the ultimate test” of a transaction’s approval.[132] The public interest framework also encompasses the banks’ compliance with fair lending and other consumer protection laws.[133]

A standard evaluation of the CRA impact of Capital One’s acquisition of Discover may surface concerns that the deal could jeopardize $300 million in Discover community development loans and investments, including affordable housing investments made under CRA.[134]

While the Federal Reserve and OCC have not outlined how job losses not linked to branch closures will be evaluated, Capital One “expect[s] to reduce Discover’s operating expenses by 26%,” to achieve its targeted $1.3 billion in operating expense synergy by 2027.[135] And with Discover’s largest operating expense its employee compensation, at around 40% of its $6 billion operating expenses in 2023, job cuts are all but assured.[136] One fintech analyst estimated the initial elimination of around 1,200 positions;[137] likewise, around 1,000 Discover jobs maintained in Delaware may be at risk, given statements on the investor call that only Discover’s Chicago location would be maintained.[138]

Additionally, a number of community and public interest groups oppose the deal.[139]

Anti-Money Laundering

The 2001 PATRIOT Act amended federal banking statutes to require regulators to assess the merging banks’ anti-money laundering record.[140]

“The Capital One anti-money laundering (AML) enforcement action that concluded in January does for AML enforcement actions what Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Irishman’ did for gangster movies,” began a Bloomberg Law article on the firm’s 2021 Treasury penalty. “Cover most of its field’s major story lines of the past and present in a massive production packed with familiar names.”[141] The enforcement action, which resulted in a $390 million penalty for what officials described as Capital One’s “egregious” and “willful” violations of AML laws,[142] targeted compliance failures that were “elementary,” the Bloomberg analyst wrote, involving simple filings that were rarely an element of AML enforcement actions, “except those against small financial institutions with limited resources for AML compliance.”[143]

The 2021 enforcement action came after multiple prior OCC consent orders for AML failures. In 2018, the OCC levied a consent order with a $100 million penalty against Capital One, noting that the firm’s violations also breached a previous AML consent order imposed in 2015.[144]

The January 2024 OCC policy statement identified transactions where the acquirer has open or pending AML enforcement actions as an example of “indicators that raise supervisory or regulatory concerns.”

[1] “Insured U.S.-Chartered Commercial Banks That Have Consolidated Assets Of $300 Million Or More, Ranked By Consolidated Assets As of December 31, 2023,” Federal Reserve Statistical Release, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/lbr/current/default.htm.

[2] Alex Graf and Gaby Villaluz, “Auto loan delinquencies at US banks continue to rise on a year-over-year basis,” S&P Global Market Intelligence, May 25, 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/capital-one-pulls-ahead-of-ally-for-industry-s-largest-auto-loan-book-62940583.

[3] “Insured U.S.-Chartered Commercial Banks That Have Consolidated Assets Of $300 Million Or More, Ranked By Consolidated Assets As of December 31, 2023,” Federal Reserve Statistical Release, https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/lbr/current/default.htm.

[4] Caitlin Mullen, “Capital One-Discover deal may spark antitrust concern,” Payments Dive, Feb. 21, 2024, https://www.paymentsdive.com/news/capital-one-discover-acquisition-card-network-competition-antitrust/708057/.

[5] “American Credit Card Debt Hits a New Record—What’s Changed Post-Pandemic?,” Government Accountability Office, Oct. 31, 2023, https://www.gao.gov/blog/american-credit-card-debt-hits-new-record-whats-changed-post-pandemic.

[6] As measured by Return on Assets (ROA), in 2023 banks earned an average of 5.9% from credit card operations, versus an industrywide ROA average of 1.36% overall. See: “Quarterly Banking Profile: Third Quarter 2023,” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Jan. 2024, https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/fdic-quarterly/2023-vol17-4/fdic-v17n4-3q2023.pdf; “Report to the Congress on the Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 2021, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/ccprofit2021.pdf.

[7] Visa and Mastercard boast net profit margins of around 50%, compared to an S&P 500 average of 11%. See: “Can the Visa-Mastercard duopoly be broken?,” The Economist, Aug. 17, 2022, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/08/17/can-the-visa-mastercard-duopoly-be-broken; CSIMarket, “S&P 500 Profitability,” https://csimarket.com/Industry/industry_Profitability_Ratios.php?sp5.

[8] Peter Horst and Robert Duboff, “Don’t Let Big Data Bury Your Brand,” Harvard Business Review Magazine, Nov. 2015, https://hbr.org/2015/11/dont-let-big-data-bury-your-brand.

[9] Malcolm Wheatley, “Capital One Builds Entire Business on Savvy Use of IT,” CIO, Nov. 1, 2001, https://www.cio.com/article/266326/business-alignment-capital-one-builds-entire-business-on-savvy-use-of-it.html.

[10] Martin Giles, “Capital One’s Digital Diaspora: How One Bank Became A Wellspring Of CIO Talent For Many Companies,” Forbes, May 7, 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/martingiles/2021/05/07/capital-one-cio-digital-diaspora-and-it-talent/?sh=271ee984b1fa.

[11] For example, from 2005 to 2013, despite a global recession, Capital One’s compound annual growth rate significantly outperformed those of the top three U.S. banks. See: Jerome Buvat and Subrahmanyam KVJ, “Doing Business The Digital Way: How Capital One Fundamentally Disrupted the Financial Services Industry,” Capgemini Consulting, 2014, https://www.capgemini.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/capital-one-doing-business-the-digital-way_0.pdf.

[12] Anna Fiorentino et al., “Driving Intelligent Growth With Customer Value Maximization: How banks should go beyond CRM,” McKinsey (EMEA Banking Practice), Dec. 2010, available at https://silo.tips/download/driving-intelligent-growth-with-customer-value-maximization.

[13] Christopher Worley and Edward Lawler III, “Building a Change Capability at Capital One Financial,” Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2009, https://ceo.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/12_Building_a_Chg_Capability.pdf.

[14] “Capital One was one of the first card issuers to use big data decades ago to target individual customers, pioneering concepts like teaser offers and tailored interest rates, which helped it reel in and manage less-than-perfect borrowers.” See: Michelle F Davis, “Banks Are Handing Out Beefed-Up Credit Lines No One Asked For,” Bloomberg, Jan. 23, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-23/banks-are-raising-credit-card-limits-without-asking-customers.

[15] In 2023, Capital One earned $19.7 billion in net interest income from credit cards out of a total of $36.8 billion in net revenue. See: Capital One Financial Corp, Form 10-K For the Year Ended December 31, 2023, SEC filing, Feb. 24, 2023, https://ir-capitalone.gcs-web.com/static-files/994c8bec-608e-49d1-8ae2-a039bc43ba54.

[16] “Data spotlight: Credit card data: Small issuers offer lower rates,” CFPB, Feb. 16, 2024, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/credit-card-data-small-issuers-offer-lower-rates/.

[17] Capital One is also an innovator further down the debt value chain, with a uniquely aggressive debt collection program. See: Paul Kiel, “At Capital One, Easy Credit and Abundant Lawsuits,” ProPublica, Dec. 28, 2015, https://www.propublica.org/article/at-capital-one-easy-credit-and-abundant-lawsuits; also see Paul Kiel and Jeff Ernsthausen, “Capital One and Other Debt Collectors Are Still Coming for Millions of Americans,” ProPublica, June 8, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/capital-one-and-other-debt-collectors-are-still-coming-for-millions-of-americans.

[18] Ken Sweet, “Americans’ reliance on credit cards is the key to Capital One’s bid for Discover,” AP, Feb. 20, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/capital-one-discover-american-debt-credit-cards-76598912b86a2dadc0c39ab3229f2fe9.

[19] “Bank Stocks, Charts & Data: 4Q23,” The Spread Site, Feb. 16, 2024, https://www.thespreadsite.com/bank-stocks-charts-data-4q23/.

[20] Transcript: Conference call held by Capital One Financial Corporation and Discover Financial Services on February 20, 2024, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/927628/000119312524040125/d797639d425.htm.

[21] Id.

[22] “Capital One Discover Investor Presentation,” Capital One, Feb. 20, 2024, https://investor.capitalone.com/static-files/cfa11729-0aec-43dc-b531-200e250c8413.

[23] “Insured U.S.-Chartered Commercial Banks,” Federal Reserve.

[24] Discover intends to divest its $10 billion student loan business before the transaction closes. See: “Discover Financial explores sale of students loan portfolio,” Reuters, Nov. 29, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/discover-financial-explores-sale-students-loan-portfolio-2023-11-29/.

[25] Transcript, Capital One Conference Call.

[26] “Initial Thoughts on Potential COF/DFS Deal,” Piper Sandler, Feb. 19, 2024.

[27] Jack Caporal, “Credit and Debit Card Market Share by Network and Issuer,” Motley Fool, Jan. 24, 2024, https://www.fool.com/the-ascent/research/credit-debit-card-market-share-network-issuer/; Becky Pokora, “Credit Card Statistics And Trends 2024,” Forbes, March 9, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/credit-cards/credit-card-statistics/.

[28] “Our Unique Network,” Discover, https://www.discoverglobalnetwork.com/our-network/our-unique-network/.

[29] The Discover network itself is also a rewarding asset, generating “significant revenue” via interchange and network fees — around $1.78 billion in 2023 — and offering a revenue stream that carries no asset or credit risk. See: Discover Financial Services, Form 10-K For the Year Ended December 31, 2023, SEC filing, Feb. 23, 2024, p. 86, https://investorrelations.discover.com/investor-relations/financials/sec-filings/sec-filings-details/default.aspx?FilingId=17303754.

[30] Transcript, Capital One Conference Call.

[31] “Investor Presentation,” Capital One.

[32] The Durbin Amendment loophole is a product not of the bill itself but of the Federal Reserve’s implementation of the rule. The Fed specifically exempted vertically integrated “three-party systems,” leaving out card issuers that are also payment networks, including American Express and Discover. So-called “three-party systems” lack an explicitly designated interchange fee for regulators to regulate — since the issuer and network are owned by the same firm, the payment network does not charge the issuer (itself) a transaction fee. See: Darryl E. Getter, “Regulation of Debit Interchange Fees,” Congressional Research Service, May 16, 2017, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R41913.pdf; Letter from Anne Segal, American Express Managing Counsel, to Jennifer J. Johnson, Secretary, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Feb. 22, 2011, https://www.federalreserve.gov/SECRS/2011/March/20110303/R-1404/R-1404_022211_67230_584162046602_1.pdf.

[33] In 2023, Discover’s PULSE debit network processed $285 billion in transaction volume against the Discover credit network’s $224 billion. See: Discover, Form 10-K, p. 57.

[34] Transcript, Capital One Conference Call.

[35] “Within the first few years, we will move our entire debit business and a portion of our credit card business to Discover,” Fairbank said, adding later, “That is the place to make […] a significant move with all of our debit business.” Id.

[36] Hugh Son, “Jamie Dimon on Capital One’s $35.3 billion Discover acquisition: ‘Let them compete,’” CNBC, Feb. 26, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/26/jamie-dimon-on-capital-one-discover-deal-let-them-compete.html.

[37] Transcript, Capital One Conference Call, “Investor Presentation,” Capital One.

[38] 12 U.S. Code § 1828.

[39] In United States v. Philadelphia National Bank, the Supreme Court held that banking was indeed “commerce” and thus subject to the Sherman and Clayton acts. This was later codified by Congress with an amendment to the Bank Merger Act in 1966. See: United States v. Philadelphia Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321 (1963); Bank Merger Act Amendments of 1966, Pub. L. 89-356, 80 Stat. 7 (codified as amended at 12 U.S.C. 1828(c)(2018)).

[40] Hugh Son, “Capital One’s acquisition has $1.4 billion breakup fee if rival bid emerges, but none if regulators kill deal,” CNBC, Feb. 22, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/22/capital-one-discover-acquisition-has-1point4-billion-breakup-fee-for-another-buyer.html.

[41] Across all bank mergers of all sizes, the last merger denied by bank regulators was Illini Corporation’s attempted acquisition of Illinois Community Bank, in 2002. See: “Order Denying the Acquisition of a Bank Holding Company,” Federal Reserve, Dec. 23, 2002, https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/orders/2002/20021223/attachment.pdf; see also: Jeremy Kress, “Modernizing Bank Merger Review,” Yale Journal on Regulation 435, Aug. 2020, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3440914.

[42] Executive Order 14036 of July 9, 2021, “Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” 86 FR 36987, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/14/2021-15069/promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy.

[43] Josh Sisco and Victoria Guida, “DOJ to expand scrutiny of bank mergers,” Politico, June 20, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/06/20/doj-bank-mergers-00102635.

[44] “Visa and Plaid Abandon Merger After Antitrust Division’s Suit to Block,” U.S. Justice Department, Press Release, Jan. 12, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/visa-and-plaid-abandon-merger-after-antitrust-division-s-suit-block.

[45] Letter from Sen. Elizabeth Warren to FDIC Chair Gruenberg and OCC Acting Comptroller Hsu, May 17, 2023, https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2023.05.17%20Letter%20to%20FDIC%20and%20OCC%20re%20First%20Republic%20JPMorgan%20Deal.pdf.

[46] “Business Combinations under the Bank Merger Act,” OCC, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 12 CFR Part 5, Docket ID OCC-2023-0017, Jan. 29, 2024, https://www.ots.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2024/nr-occ-2024-7a.pdf.

[47] According to a former OCC counsel discussing the “significant policy issue” indicator, “OCC may decide that approving a $600 billion + Durbin-exempt institution is not good policy.” See: Michele Alt, “Will the regulators put the kibosh on a $600 billion+ deal that could create a competitive alternative to the Visa/MC payment rails?” LinkedIn, Feb. 20, 2024, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/michele-alt-42baaa50_will-the-regulators-put-the-kibosh-on-a-600-activity-7165834722609225728-vrQy/.

[48] Letter from Sen. Elizabeth Warren to FDIC Chair Gruenberg and OCC Acting Comptroller Hsu, Feb. 25, 2024, https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2024.02.25%20Capital%20One%20Letter1.pdf.

[49] Letter from Rep. Maxine Waters to Regulators, Feb. 28, 2024, https://democrats-financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/02.28_-_ltr_on_ibmr.pdf.

[50] Letter from Sen. Josh Hawley to Assistant Attorney General Kanter, Feb. 21, 2024, https://www.hawley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/2024-02/Hawley-Letter-to-Kanter-re-Capital-One-Discover-Merger.pdf.

[51] “2023 Merger Guidelines,” U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Federal Trade Commission, Dec. 18, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/d9/2023-12/2023%20Merger%20Guidelines.pdf.

[52] Id.

[53] Id.

[54] Large Holding Companies, Federal Reserve Data, 2022, https://www.ffiec.gov/npw/Institution/TopHoldings.

[55] Naeem, “Revitalizing Bank Merger Enforcement.”

[56] Id.

[57] “2023 Merger Guidelines,” DOJ & FTC.

[58] Kevin Wack, “The biggest bank M&A deals of the last decade,” American Banker, March 16, 2022, https://www.americanbanker.com/list/the-biggest-bank-m-a-deals-of-the-last-decade.

[59] Written Testimony of Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., “Hearing On Credit Card Practices: Current Consumer

And Regulatory Issues,” House Financial Services Committee Subcommittee On Financial Institutions And Consumer Credit, April 27, 2007, https://www.law.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs5421/files/downloads/WilmarthTestimonyonCreditCardIndustry4.26.07.pdf; Duncan A. MacDonald, “Viewpoint: Card Industry Questions Congress Needs to Ask,” American Banker, March 23, 2007.

[60] Poonkulali Thangavelu, “Credit card market share statistics,” Bankrate, July 6, 2023, https://www.bankrate.com/finance/credit-cards/credit-card-market-share-statistics/#balance; “The Consumer Credit Card Market,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, October 2023, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2023.pdf.

[61] Dan Martinez and Margaret Seikel, “Credit card interest rate margins at all-time high,” CFPB, Feb. 22, 2024, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/credit-card-interest-rate-margins-at-all-time-high/.

[62] “CFPB Report Finds Large Banks Charge Higher Credit Card Interest Rates than Small Banks and Credit Unions,” CFPB, Feb. 16, 2024, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-report-finds-large-banks-charge-higher-credit-card-interest-rates-than-small-banks-and-credit-unions/.

[63] “CFPB Report Finds Large Banks Charge Higher Credit Card Interest Rates than Small Banks and Credit Unions,” CFPB, Feb. 16, 2024, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-report-finds-large-banks-charge-higher-credit-card-interest-rates-than-small-banks-and-credit-unions/; “CFPB Report Finds Credit Card Companies Charged Consumers Record-High $130 Billion in Interest and Fees in 2022,” CFPB, Oct. 25, 2023, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-report-finds-credit-card-companies-charged-consumers-record-high-130-billion-in-interest-and-fees-in-2022/.

[64] Wilmarth, Jr., Testimony, “Hearing on Credit Card Practices.”

[65] “Can the Visa-Mastercard duopoly be broken?,” The Economist, Aug. 17, 2022, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/08/17/can-the-visa-mastercard-duopoly-be-broken.

[66] The feature also noted that despite a “trifecta of threats” from Congress, cryptocurrencies, and financial-technology companies, thoughts of Visa and Mastercard’s “impending doom” were unrealistic: “their position remains strong.” See: Joe Light, “Visa and Mastercard Are Under Attack. They Will Do Just Fine.” Barron’s, Aug. 16, 2023, https://www.barrons.com/articles/visa-mastercard-are-under-attack-they-will-do-just-fine-7d2e67ce.

[67] See: Joe Light, “Visa and Mastercard Are Under Attack. They Will Do Just Fine.” Barron’s, Aug. 16, 2023, https://www.barrons.com/articles/visa-mastercard-are-under-attack-they-will-do-just-fine-7d2e67ce.

[68] Caporal, “Credit and Debit Card Market Share.”

[69] Kress, “Modernizing Bank Merger Review.”

[70] “Terms of Credit Card Plans (TCCP) Survey, Data Download: Jan. 1 – June 30, 2023,” CFPB, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/credit-card-data/terms-credit-card-plans-survey/.

[71] Dan Ennis, “American Express catches up to Visa, Mastercard in acceptance,” Retail Dive, Jan 28, 2020, https://www.retaildive.com/news/american-express-catches-up-to-visa-mastercard-in-acceptance/571168/

[72] Angel Au-Yeung, “Visa, Mastercard Prepare to Raise Credit-Card Fees,” The Wall Street Journal, Aug 30, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/finance/visa-mastercard-prepare-to-raise-credit-card-fees-ed779be1

[73] According to Nilson Report data, in 2012 businesses paid $32.73 billion in interchange fees against a total of $2.26 trillion in U.S. credit card spending, this compares to 2021, where businesses paid $93.2 billion in fees on $4.6 trillion of spending. See: Au-Yeung, “Visa, Mastercard Prepare to Raise Credit-Card Fees;” also see: “Value of credit card transactions for payments in the United States from 2012 to 2021,” Statista, Jan 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/568554/credit-debit-card-transaction-value-usa/

[74] “By shifting its debit volume to Discover’s network, Capital One can charge merchants higher fees, which could lead to around $800 million of pre-tax earnings upside based on estimated debit volumes of $90 billion.” See: Marc Rubenstein, “The Third Network,” Net Interest, Feb 23, 2024, https://www.netinterest.co/p/the-third-network.

[75] “2023 Merger Guidelines,” DOJ & FTC.

[76] In its successful challenge to JetBlue’s acquisition of Spirit Airlines, the Justice Department argued that merger would eliminate Spirit’s “ultra-low cost” model, removing choice for budget-conscious consumers and raising prices kept in check by a lower-price competitor. See United States v. JetBlue Airways Corp., No. 23-10511, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (Dkt. 461), at 101-105 (D. Mass. Jan. 16, 2024).

[77] Annual filings for JPMorgan show $29.5 billion in subprime card loans, around 14% of its card lending; Citi, $33.6 billion subprime at 20% of card lending (note that Citi reports subprime as FICO below 680); Capital One at $47 billion and 32% respectively; and Discover at $20 billion and 20% respectively. See: JPMorgan Chase & Co., Form 10-K For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2023, SEC, p. 247, https://jpmorganchaseco.gcs-web.com/static-files/65230b3c-57f5-4e9e-9d68-e4a51a418ed4; Citigroup Inc., Form 10-K For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2023, SEC, p. 219, https://www.citigroup.com/rcs/citigpa/storage/public/10k20231231.pdf; Capital One, Form 10-K, p. 66; Discover, Form 10-K, p. 102.

[78] Id.

[79] Jeremy Kress (@Jeremy_Kress), tweet posted Feb. 26, 2024, https://x.com/Jeremy_Kress/status/1762576947761279089?s=20.

[80] Eighty percent of Discover’s credit card lending is to cardholders with FICO scores above 660, while for Capital One that number is 68%. See: Capital One, Form 10-K; Discover, Form 10-K.

[81] Wayne Duggan, “What Investors Should Know About the Capital One-Discover Deal,” US News, Feb. 21, 2024, https://money.usnews.com/investing/articles/what-investors-should-know-about-the-capital-one-discover-deal; Liz Kiesche, “Analysts dig into the $35B Capital One/Discover Financial deal,” Seeking Alpha, Feb. 20, 2024, https://seekingalpha.com/news/4069115-analysts-dig-into-the-capital-onediscover-financial-35b-deal; Claire Williams and Polo Rocha, “The Capital One-Discover deal raises thorny issues for Washington,” American Banker, Feb. 20, 2024, https://www.americanbanker.com/news/the-capital-one-discover-deal-raises-thorny-issues-for-washington.

[82] Elena Botella, “A Capital One – Discover Merger Could Raise Card Interest Rates,” Forbes, Mar 16 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/elenabotella/2024/03/16/a-capital-onediscover-merger-could-raise-card-interest-rates

[83] Id.

[84] “2023 Merger Guidelines,” DOJ & FTC.

[85] United States v. JetBlue Airways Corp., No. 23-10511, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (Dkt. 461), at 101–105 (D. Mass. Jan. 16, 2024).

[86] “Value of card transactions with Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover in the United States from 2010 to 2022,” Statista, Feb. 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/678109/purchase-volume-payment-cards-usa-by-type/; Caporal, “Credit and Debit Card Market Share.”

[87] Id.; Hearing, California Assembly Banking & Finance Committee, Jan. 25, 2010, https://abnk.assembly.ca.gov/sites/abnk.assembly.ca.gov/files/hearings/01_25_10_The_Evolution_of_InterchangeFeesreport.pdf.

[88] Transcript, Capital One Conference Call.

[89] Caitlin Mullen, “Capital One angles to push Discover upmarket,” Payments Dive, March 7, 2024, https://www.paymentsdive.com/news/capital-one-discover-upmarket-card-network-acquisition-credit-debit-acceptance/709592/.

[90] Sanjay Sakhrani, Interview on BNN Bloomberg, Feb. 20, 2024, https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/video/it-makes-a-lot-of-sense-for-capital-one-to-buy-discover-financial-analyst~2870490.

[91] Caporal, “Credit and Debit Card Market Share.”

[92] Lynne Marek, “Mastercard to be dinged by Discover deal,” Payments Dive, Feb. 21, 2024, https://www.paymentsdive.com/news/mastercard-visa-discover-acquisition-bank-card-network/708060/.

[93] “Where are Discover Credit Cards Accepted?,” Discover, Nov. 26, 2023, https://www.discover.com/credit-cards/card-smarts/discover-cards-acceptance/.

[94] “2023 Merger Guidelines,” DOJ & FTC.

[95] Jonathan Kanter, “Digital Markets and ‘Trends Towards Concentration,’” Journal of Antitrust Enforcement, Volume 11, Issue 2, July 2023, 143–148, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jnad030.

[96] 12 U.S.C. § 1828(c)(5).

[97] “2023 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs),” Financial Stability Board, Nov. 27, 2023, https://www.fsb.org/2023/11/2023-list-of-global-systemically-important-banks-g-sibs/.

[98] “Business Combinations under the Bank Merger Act,” OCC.

[99] Id.

[100] “Banks are more complex when they engage more in activities that are more sophisticated and innovative, making them different from the average bank in the financial system.” See: Frank Hong Liu et al., “Why Banks Want to Be Complex,” The American Economic Association, 2016, https://repositorio.fgv.br/server/api/core/bitstreams/b5edd8f9-f736-4d50-aeef-18e7981d6e2b/content.

[101] Letter from Sen. Warren to Chair Gruenberg and Acting Comptroller Hsu.

[102] Daniel K. Tarullo, “Regulators should rethink the way they assess bank mergers,” The Brookings Institution, March 16, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/regulators-should-rethink-the-way-they-assess-bank-mergers/.

[103] Order Approving the Merger of Bank Holding Companies, the Merger of Banks, and the Establishment of Branches, Federal Reserve FRB Order No. 2021–08, Jun 10, 2021, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/files/orders20210610a1.pdf.

[104] With $625 billion in assets, Capital One-Discover would be larger than all three regional banks that failed in the spring of 2023 combined.

[105] Michael Barr, “Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank,” Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve, April 28, 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/svb-review-20230428.pdf.

[106] Evan Weinberger, “Fed, FDIC Need to Fix Bank Supervision Problems, Watchdog Says,” Bloomberg Law, March 6, 2024, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/banking-law/fed-fdic-need-to-fix-bank-supervision-problems-watchdog-says.

[107] “Statement of CFPB Director Rohit Chopra, Member, FDIC Board of Directors, at the FDIC Systemic Resolution Advisory Committee,” CFPB, Nov. 9, 2022, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/statement-of-cfpb-director-chopra-at-fdic-systemic-resolution-advisory-committee/.

[108] “Top Management and Performance Challenges Facing the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation,” FDIC Office of Inspector General, Feb. 2024, https://www.fdicoig.gov/sites/default/files/reports/2024-02/TMPC-Final-Feb24.pdf.

[109] “Business Combinations under the Bank Merger Act,” OCC.

[110] Mayra Rodriguez Valladares, “Capital One Should Not Rush To Acquire Discover,” Forbes, Feb. 22, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/mayrarodriguezvalladares/2024/02/22/capital-one-should-not-rush-to-acquire-discover/.

[111] “Credit card loans represent 47% of Capital One’s loan portfolio […] Discover’s credit card portfolio represents an even higher percent of its loan portfolio at 79%.” See: Rodriguez Valladares, “Capital One Should Not Rush,” also see SEC Form 10-K, Capital One Financial Corp, filed Feb. 24, 2023, https://ir-capitalone.gcs-web.com/static-files/994c8bec-608e-49d1-8ae2-a039bc43ba54; SEC Form 10-K, Discover Financial Services, filed Feb. 23, 2023, https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001393612/9aaafe03-0512-424d-a775-7f8c01a768e2.pdf.

[112] Lorenzo Migliorato, “Discover, Capital One loans ravaged by Fed stress test,” Risk.net, June 29, 2020, https://www.risk.net/risk-quantum/7648261/discover-capital-one-loans-ravaged-by-fed-stress-test.

[113] Hugh Son, “Federal Reserve says 23 biggest banks weathered severe recession scenario in stress test,” CNBC, June 28, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/28/fed-stress-test-2023-23-banks-weathered-severe-recession.html.

[114] Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, 2023:Q4, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Feb. 6 2024, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2023Q4.

[115] Paige Smith, “Capital One Charge-Offs Jump on Auto, Credit Card Write-Downs,” Bloomberg, Jan. 25, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-25/capital-one-charge-offs-jump-on-auto-credit-card-write-downs; Kate Fitzgerald, “Discover’s credit card charge-offs overshadow strong loan growth,” American Banker, Jan. 19, 2023, https://www.americanbanker.com/payments/news/discovers-credit-card-charge-offs-overshadow-strong-loan-growth.

[116] “Bank Stocks, Charts & Data: 4Q23,” The Spread Site.

[117] John Heltman, “Capital One-Discover merger pits concentration risk against payments competition,” American Banker, Feb. 20, 2024, https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/capital-one-discover-merger-pits-concentration-risk-against-payments-competition.

[118] Santul Nerkar, “What’s Behind the Turmoil at New York Community Bank?,” The New York Times, March 1, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/01/business/new-york-community-bank.html.

[119] Caitlin Mullen, “Discover shares pricing error findings with regulators,” Payments Dive, Sept. 13, 2023, https://www.paymentsdive.com/news/discover-cfo-john-greene-card-pricing-error-investigation-regulators-fdic/693465/.

[120] Id.

[121] Ben Miller, “Discover Leaders Sued Again Over Compliance Issues, Stock Drops,” Bloomberg Law, Oct. 6, 2023, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/litigation/discover-leaders-sued-again-over-compliance-issues-stock-drops.

[122] “Discover Bank, The Student Loan Corporation, and Discover Products, Inc.,” CFPB Enforcement Actions, Docket #2020-BCFP-0026, Dec. 22, 2020, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/enforcement/actions/discover-bank-the-student-loan-corporation-and-discover-products-inc/.

[123] Caitlin Mullen, “Discover, FDIC reach consent agreement,” Payments Dive, Oct. 2, 2023, https://www.paymentsdive.com/news/discover-fdic-consent-agreement-compliance-consumer-protection-risk-regulators/695302/.

[124] “2011 Annual Report,” Capital One, 2011, https://investor.capitalone.com/static-files/8f64ab9f-4df7-4ab7-a321-5cc380bec44a.

[125] Federal Reserve Merger Approval Order – Capital One Financial Corporation and ING Direct Investing, Inc. Feb. 14, 2012, pp. 13 & 39, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/files/order20120214.pdf.

[126] “FinCEN Announces $390,000,000 Enforcement Action Against Capital One, National Association for Violations of the Bank Secrecy Act,” U.S. Treasury FinCEN, Jan. 15, 2021, https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-announces-390000000-enforcement-action-against-capital-one-national.

[127] Renata Geraldo, “No prison for Seattle hacker behind Capital One $250M data breach,” The Seattle Times, Oct. 4, 2022, https://www.seattletimes.com/business/no-prison-for-seattle-hacker-behind-capital-one-250m-data-breach/.

[128] “Department Secures Settlements with CarMax, Axis Analytics, Capital One Bank and Walmart for Posting Discriminatory Job Advertisements on College Recruiting Platforms,” U.S. Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, Sept. 21, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-secures-settlements-carmax-axis-analytics-capital-one-bank-and-walmart.

[129] Capital One meets stated criteria for “multiple enforcement actions against the bank executed or outstanding during a three-year period.” See: “OCC Revises Bank Enforcement Manual to Address Actions Against Banks with Persistent Weaknesses,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, May 25, 2023, https://www.occ.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2023/nr-occ-2023-49.html.

[130] “Business Combinations under the Bank Merger Act,” OCC.

[131] 12 U.S. Code § 1828.

[132] United States v. Third Nat’l Bank of Nashville, 390 U.S. 171 (1968); Kress, “Modernizing Bank Merger Review.”

[133] Kress, “Modernizing Bank Merger Review.”

[134] Discover Bank’s CRA Strategic Plan 2023-2027, “Discover to add jobs in Delaware,” Delaware Business Times, Sept. 15, 2022, https://delawarebusinesstimes.com/news/discover-to-add-jobs/.

[135] Capital One CFO Andrew M. Young on the Feb. 20 investor call.

[136] Discover 10-K, p. 86.

[137] “[L]egacy Discover leadership has a 20% representation in decision making. Translated to the personnel, when I do the math it means this combined workforce is going to need to take at least a 6% cut. […] Right now the workforce distribution is closer to 26/74.” See: Zarik Khan, “Capital One buys Discover – now what?,” Fintech Compliance Chronicles, Feb. 22, 2024, https://fintechcompliance.substack.com/p/capital-one-buys-discover-now-what.

[138] Jacob Owens, “Discover to add jobs in Delaware,” Delaware Business Times, Sept. 15, 2022, https://delawarebusinesstimes.com/news/discover-to-add-jobs/.

[139] “NCRC Opposes Capital One-Discover Merger,” National Community Reinvestment Coalition, Feb. 20, 2024, https://ncrc.org/ncrc-opposes-capital-one-discover-merger/; Anthony Noto, “Is Capital One Next? Corporate Deals Are Getting Nixed As M&A Scrutiny Intensifies,” Global Finance Magazine, March 7, 2024, https://gfmag.com/capital-raising-corporate-finance/mergers-acquisitions-blocked-regulators-capital-one-discover/.

[140] Kress, “Reviving Bank Antitrust.”

[141] Robert Kim, “Capital One Case Teaches Old and New AML Lessons,” Bloomberg Law, Jan. 29, 2021, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/bloomberg-law-analysis/analysis-capital-one-case-teaches-old-and-new-aml-lessons.

[142] “FinCEN Announces $390,000,000 Enforcement Action Against Capital One, National Association for Violations of the Bank Secrecy Act,” U.S. Treasury FinCEN, Jan. 15, 2021, https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-announces-390000000-enforcement-action-against-capital-one-national.

[143] Id.

[144] Robert Armstrong, “Capital One fined $100m over anti-money laundering controls,” Financial Times, Oct. 23, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/7b716658-d6f2-11e8-ab8e-6be0dcf18713.